The Carson Sink is the terminal basin of the Carson River, draining from the Sierra into western Nevada. The sink is also, at times, the terminus of the Humboldt River; in years of high winter precipitation, the combined flows can result in an expansive, shallow lake in the typically barren sink. And yet, even in dry times, the Stillwater Marshes — a National Wildlife Refuge — reach into the basin at the delta of the Carson River. The life-giving and ever-changing wetlands have been the homeland of North Paiute people and communities for millennia; the still are.

Although the sink is relatively close to home, I have spent more time in the surrounding ranges and valleys than I have looking into the vast desert basin. I am beginning to take a closer look at the landforms, their timing and process, of this distal basin and an overland journey and geo-recce was in order. A pre-holiday storm dominated the forecast, so there could not be a better time for this trip.

Darren — my brother — and I turned off Highway 95 and onto the dirt track on the northern margin of the sink, along the toe slopes of the West Humboldt Range which separates the Carson and Humboldt drainages. The blue sky seemed to hide any evidence of the coming storm. Our traverse took us across desert fans where dusty badlands intersected the soft, effervescent playa of the former lakebed. We were alone and would be for the next few days.

We set camp south of Chocolate Butte on a series of bars and berms formed when Pleistocene-age, pluvial Lake Lahontan cut into the Buena Vista Hills. Our perch provided an overlook of the western sink with Lone Rock, a buried volcanic plug that protrudes from the playa, rising like a beacon. The landform, so significant to the Paiute people, captured our attention with sunset and at sunrise following.

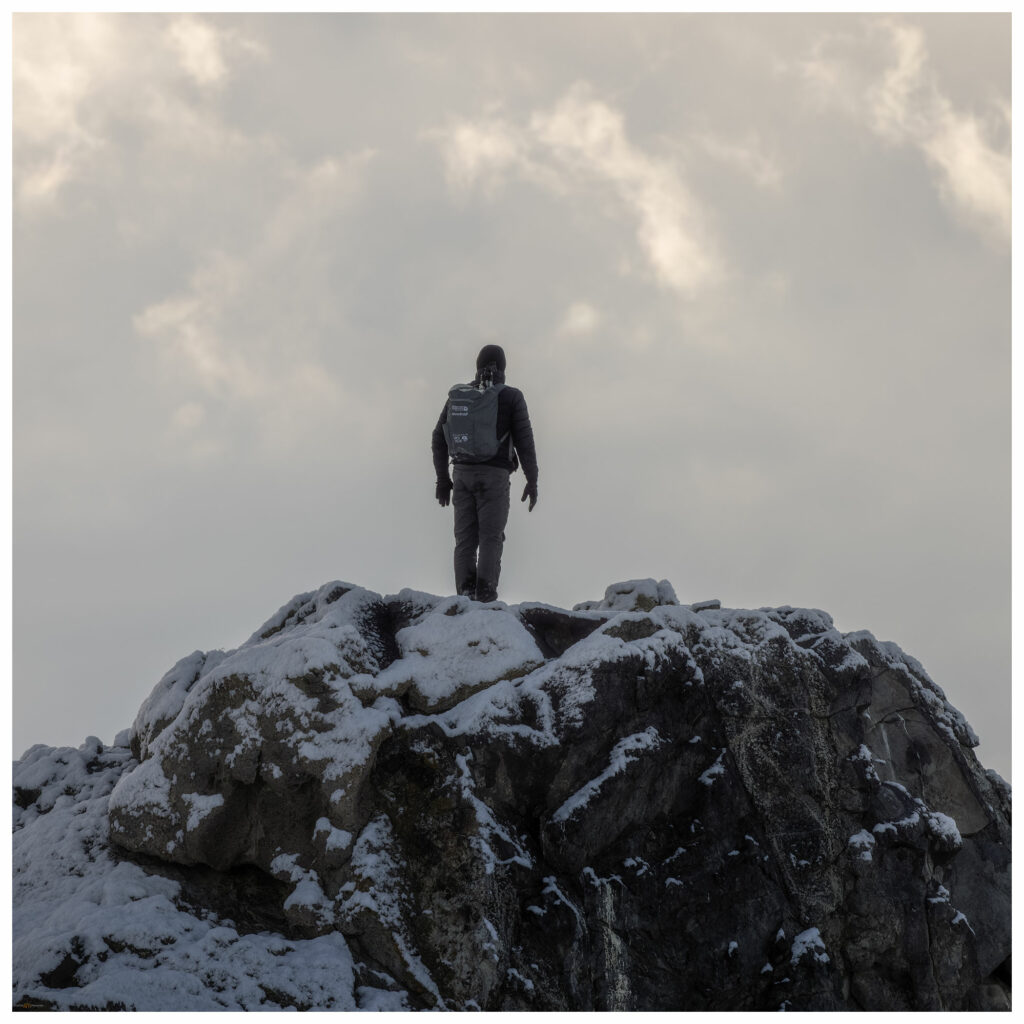

The snow came in the night. Hearing the quiet that sometimes hints at morning fog, I looked out of the camper to see three inches of new snowfall. The desert landscape was now a white expanse, a few dark hills standing in relief. We wandered the old lake strands and berms under dramatic clouds with fog-laden breaks underneath.

The squalls seemed to be breaking up by mid-morning. Under clearing skies we made some breakfast on the skottle, re-loaded our coffee, and secured camp for the day. It had been many years since I had traversed the western bajada of the Stillwater Mountains — the bajada formed of numerous alluvial fans emanating from the many canyons along the mountain front. The coalesced fans form a two-tiered apron below the mountain and lead to a sand dune that piles and re-piles along the margin of the playa. Wind transports sand, momentarily paused in the dune-form, but water is the sand’s source. The delta is downwind where the river, mostly the Carson, sometimes the Walker, and maybe, though long ago, the Truckee, delivered sand to the fluctuating lake. The conveyor is still operating, but it has been running on little energy since the Pleistocene. Southerly winds, with the occasional redirection of a north-westerly storm pulse, push the sand to the valley margins. Starving for sediment, the dunes are now their own sand source, with new parabolic racers leaving exposed dune-core badlands in relief. Traversing the high sand faces and walking quietly through the skeletal-core, we soon encroach the playa expanse.

Our second night is long and cold. The darkness of the Winter Solstice is almost upon us; nightfall is early and we pass the long hours of the evening with a camp dinner and a quiet fire. The Geminids meteor shower teases disappointingly, so we share stories and plans for the new year — ways to make the most of our time in the pandemic. Outback travel continues to seed hope and heal with a bit of distraction.

A second storm approaches on Sunday morning. We pack camp and continue southward; today entering the east side of the Stillwater Marshes so that we can cross the delta from east to west before once again hitting the highway. Rain squalls come and go as we traverse the silt dunes of the North Road and finally venture into recent snow-cover at Papoose Lake.

I will have several field seasons of work coming in the geography of the Carson Sink. This refresher overland re-set my thinking and provided a new foundation for investigating the open space surrounding that vast playa.

Keep going.

Please respect the natural and cultural resources of our public lands.

Leave a Reply