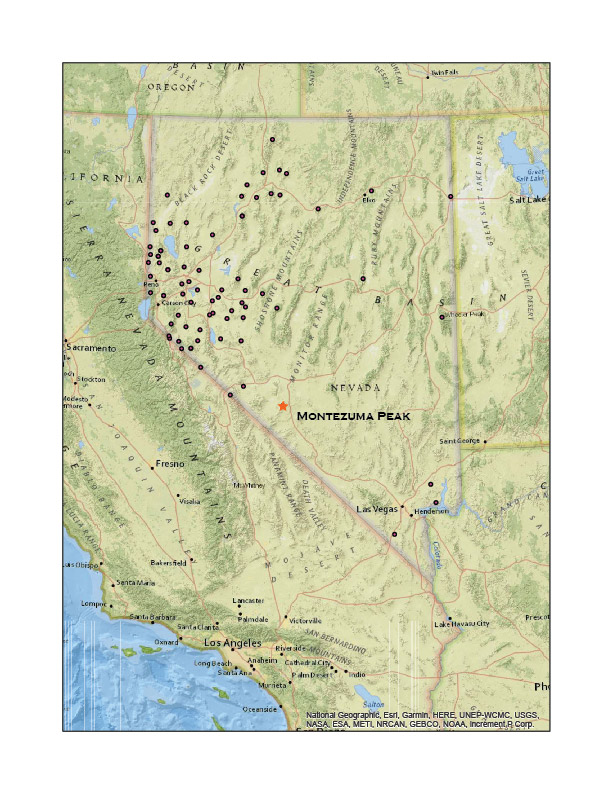

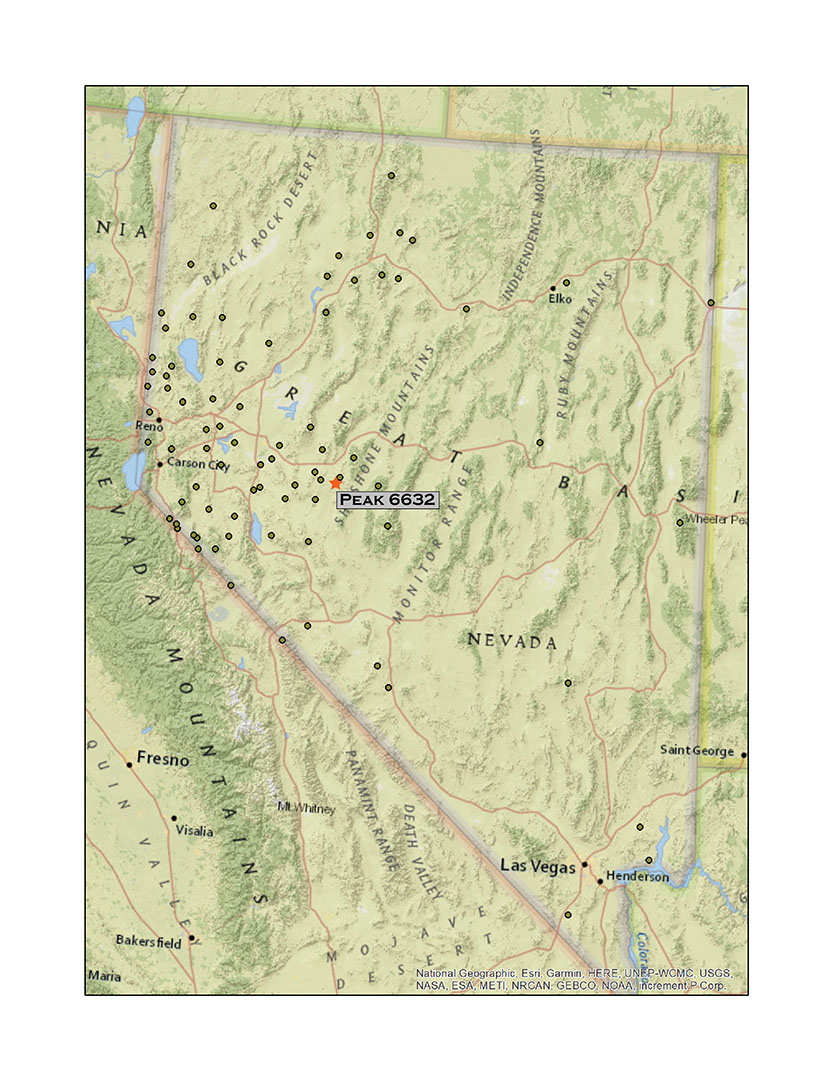

Peak 6632

6632 ft (2021 m) – 600 ft gain

2021.07.10

It has been a strange week, but maybe this is just how they are now. A 5.9-magnitude earthquake shook our house, Portland hit 113° (and Gardnerville not much less), the Beckwourth Fire Complex continues to rampage, and monsoon-like storms knocked the power out at StoneHeart. The latter occurred after I had left on a Second Friday excursion targeting the High Rock Country. I had met Darren at his house just as Des described a powerful storm cell at home – a lightning strike resulted in a local power outage. She said it was intense but not that unusual, so Darren and I headed north toward Gerlach. But at Nixon, on the shores of Pyramid Lake, Des let me know that the power had returned but the well had not. We tried various fixes, but it would not kick in. Although our well contractor is always quick to respond, I would not rest easy in the backcountry without the water on at StoneHeart. We turned back.

However, Second Friday still goes – even if it is now Saturday. Waiting through the punishing heat of the day, Darren and I finally set out eastward on Highway 50 in early evening. We have a new plan for the short excursion. We will avoid the heat as much as possible, climbing at night and in the early morning to get high points of two smaller ranges in west-central Nevada.

It is 106° in Dayton Valley but a thunderstorm squall at Lahontan Reservoir drops the temperature along with a brief heavy rain. For a few minutes it is 76°. By the time we reach Fallon, however, it is a cloudy 104°, and it stays that way into the evening even as we hit the dirt tracks of the Broken Hills slightly higher in the Great Basin desert.

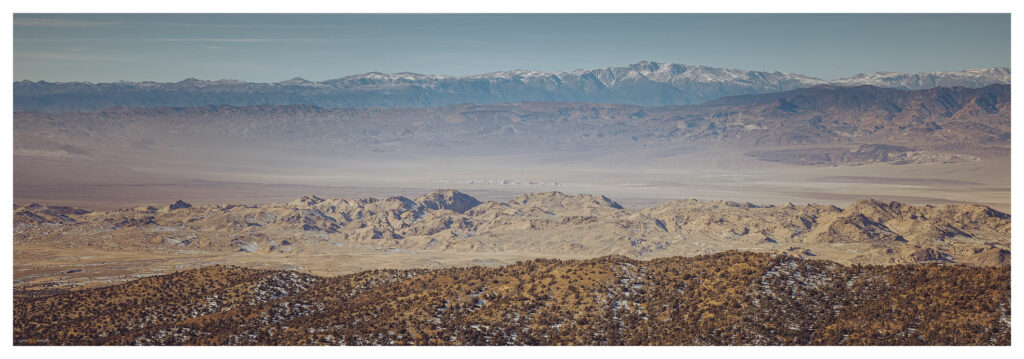

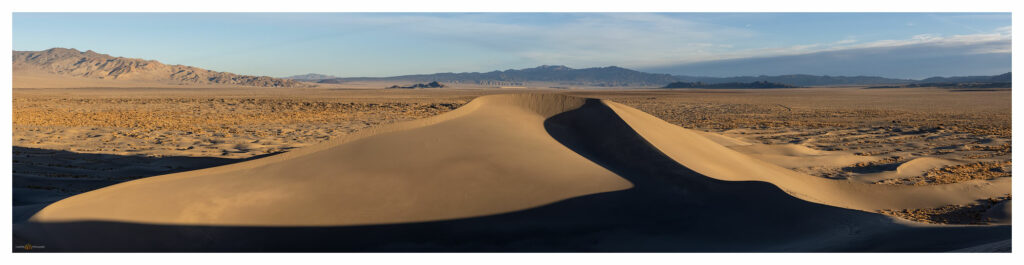

Ragged hills of rhyolite and volcanic tuffs comprise the unorganized range of the Broken Hills. On the edge of the hills, the site of Broken Hills saw a brief boom as silver discoveries drew miners to the area in the late 19th and early 20th century. McLane writes that the hills are named for either the mining district – a call to prosperous mining area in Australia – or the disparate, broken nature of the knolls, outcrops, and hummocks that make up the small, east-west-trending range. A sagebrush community forms a low-density cover with widely spaced small plants on local hillsides. There are very few trees. These are clustered in small stands of Utah juniper, typically one or two trees standing lonely along contacts between the rhyolitic rocks and volcanic tuffs, it seems. Pinyon can be found in the wash separating the Broken Hills from the East Gate Range, where the pines form a thick woodland subject to recent patchy wildland fire. The boundary between the two ranges is structural – the East Gate Range being a relatively clear north-south fault block extending away from the Desatoya Mountains, while the Broken Hills appear random and rolling. The high points of the two ranges are only a few miles apart, so our camp at Mud Springs should provide a quick base for two short climbs.

As we set camp, the smoke from the Beckwourth Complex alters the western sky. Storms struggle in virga, as gray curtains evaporate in the heat without nourishment. We make dinner and wait for the relative cool of night. It is 10 PM when we set out with headlamps, leaving the truck on a side-road a ridge away from camp. We have arachnids immediately. Scorpions and fierce-looking spiders patrol beneath our headlamps, dodging our footfalls and we dodging them. A black widow has strung a hopeful trap across one rut of our two-track path, a reminder that the hunters are busy in the understory and best to keep the headlamps and attention on. This desolate path to Peak 6632, unremarkable in daytime, is bustling after dark.

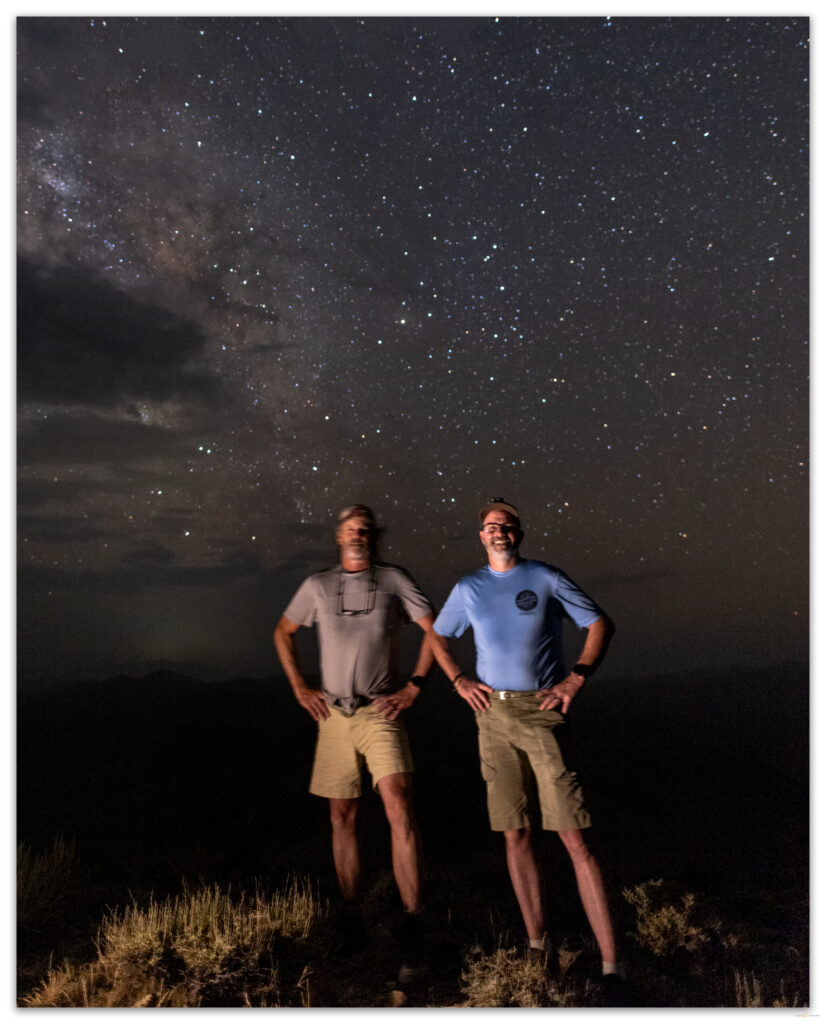

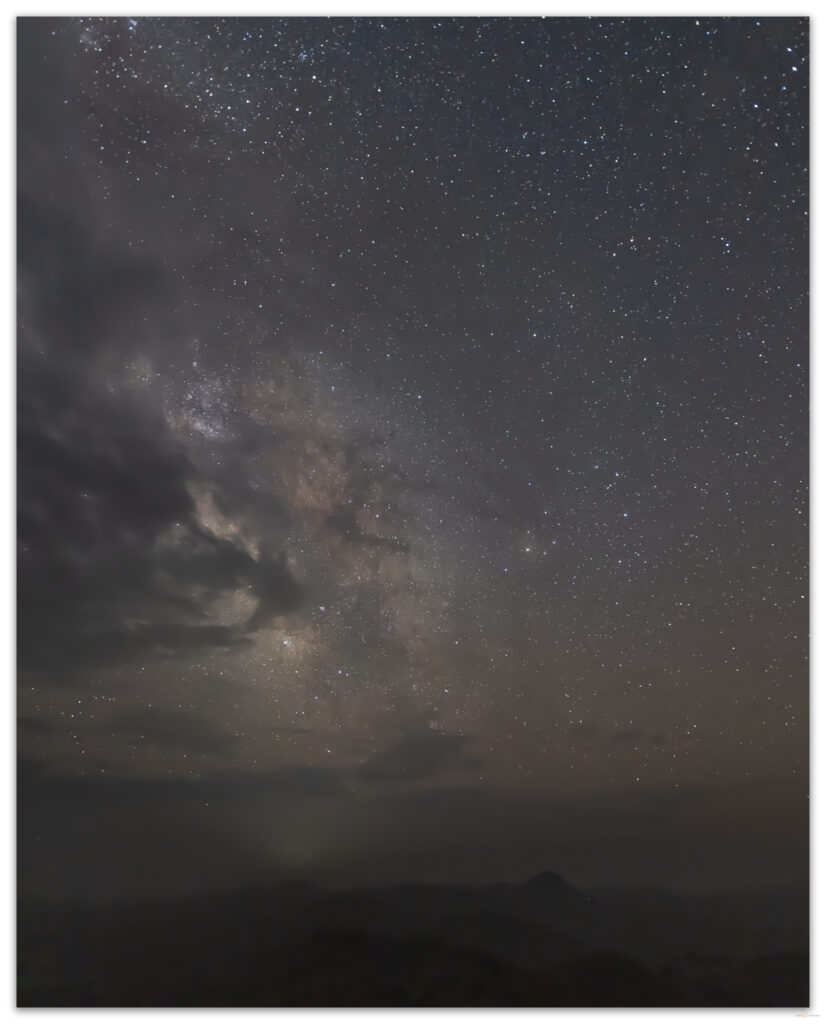

The dome of Peak 6632 steepens considerably in its final 500 feet. Darren finds the small summit cairn and we complete our first night-time summit. And it is dark as night. Clouds and smoke mute any meager light, and we realize, with no stars to guide us, we have lost our bearings. The smokey haze fills the horizon like ground-fog, and the glow of distant towns and bigger cities is almost imperceptible. Finally succumbing to checking GPS, we are baffled by our confused dead-reckoning. A moment ago, we had, with certainty, thought we were facing south, only now do we realize that that direction is north; we were 180° off. Soon, however, the parting clouds reveal the Milky Way core, and we are grounded again. A large scorpion watches our confusion – it too likely confused by our curious illumination – and we keep an eye on it as we check the summit register.

We linger for an hour or more. As the smoke blurs the shadows of hills and horizon below us, the Milky Way appears hauntingly among the clouds. Forgetting the ground-hunting creatures for a while, we turn off our headlamps to feel the dark. The wind is warm and tastes sadly of distant embers. Again, a small hill, an otherwise no-name place of interest to so few, provides a unique experience that is the dividend of motivation and the simple desire to explore the forgotten backcountry.

Keep going.

Please respect the natural and cultural resources of our public lands.