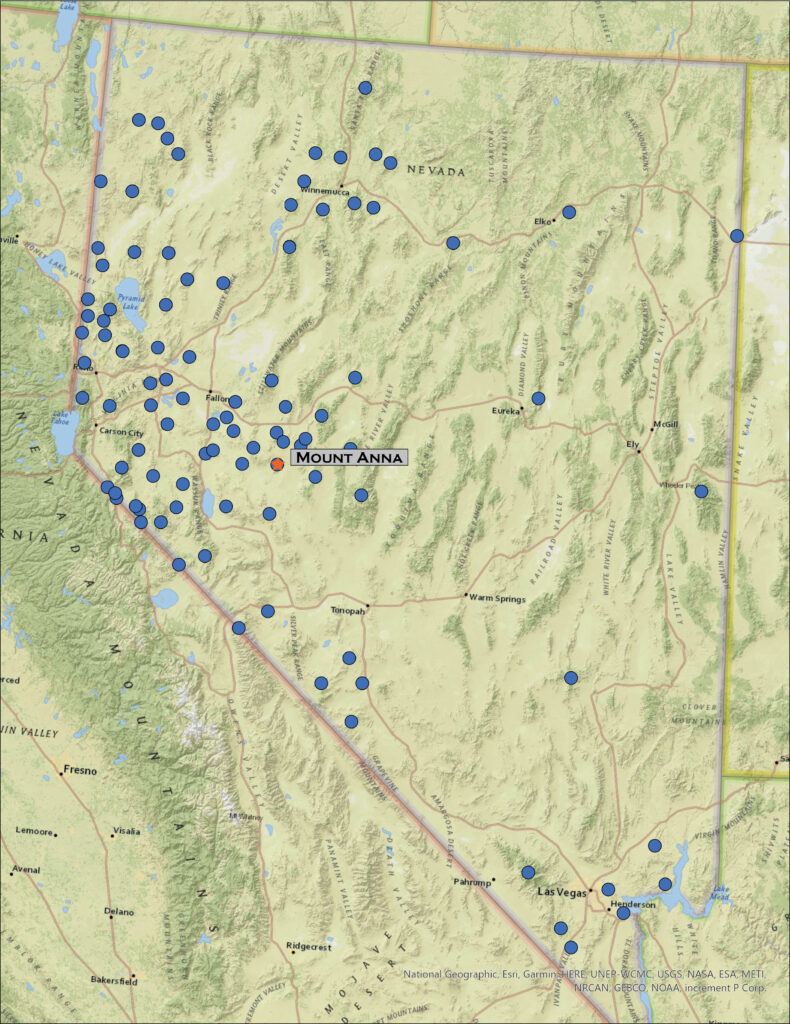

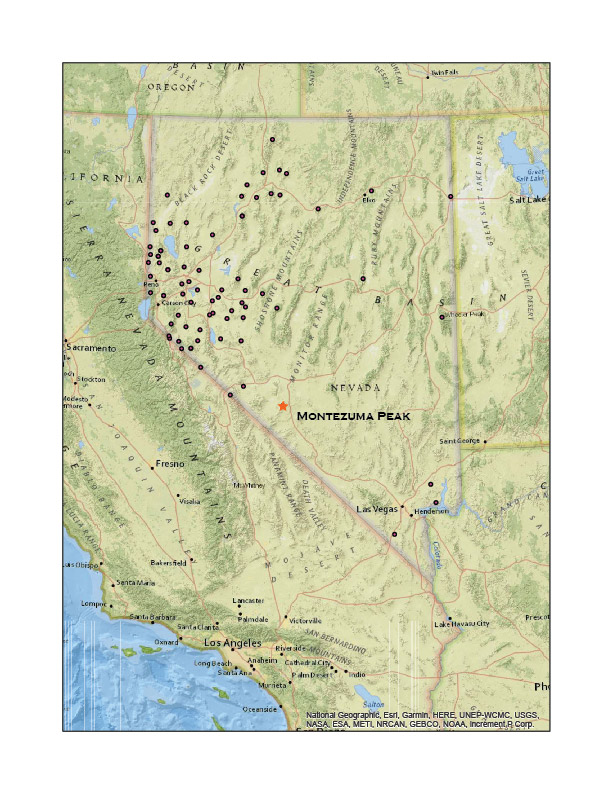

It is once again ‘Second Friday’, time for an overland. Darren and I hit Highway 50 in the late morning, expecting the forecasted wind to catch up with us later in the day. A storm was forecast but from the look of the clear skies, it was somewhere to the northwest. Planning for the weather change, I had chosen Mount Anna in the Monte Cristo Mountains bounding northern Gabbs Valley as our target. Our goal this year is to explore the ranges across central Nevada and this is a rather easy start.

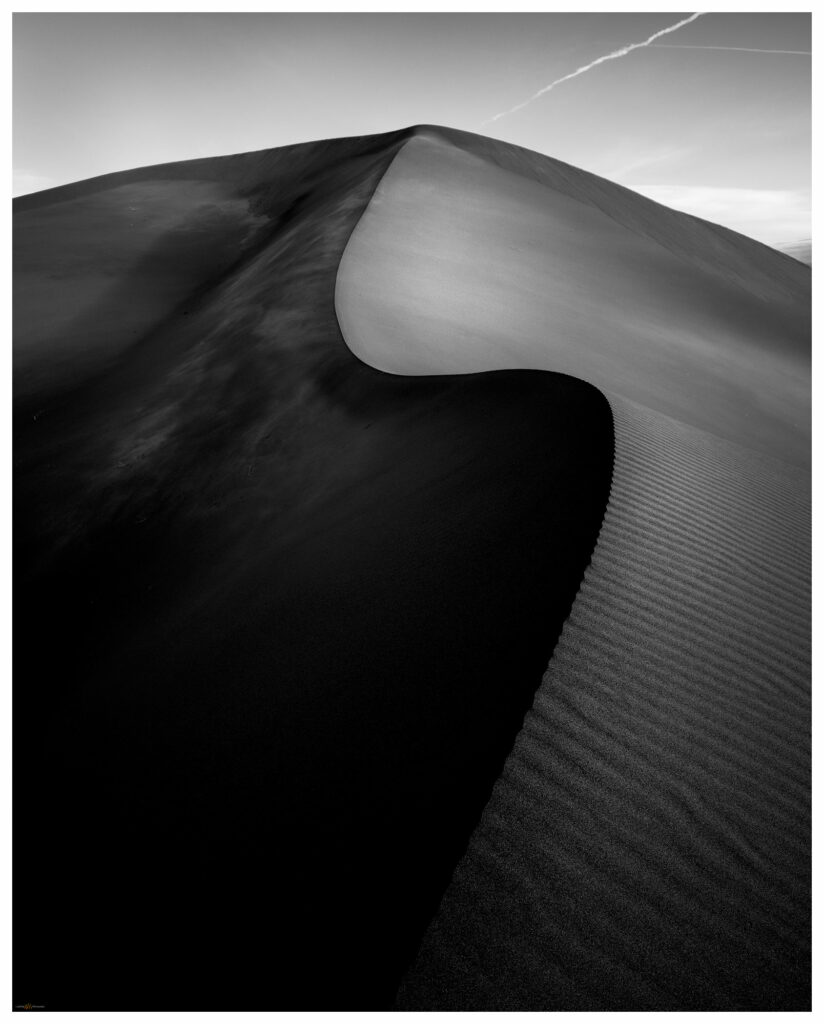

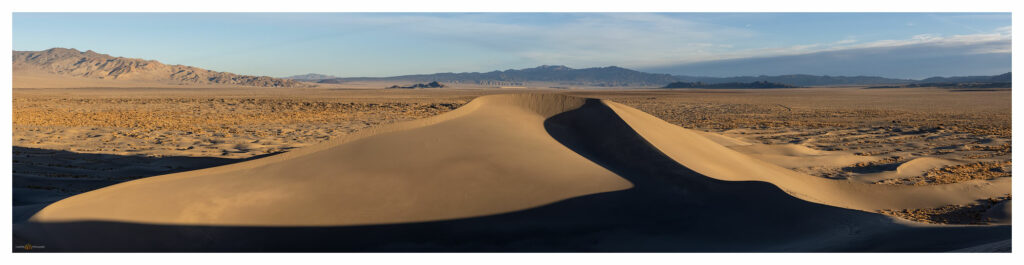

We turn south at Middlegate to traverse the low pass above Gabbs Wash and the valley expands before us. The Monte Cristos rise as a volcanic crease in the midst of Gabbs Valley, between Rawhide Flat and the hog-back of the Cobble Cuesta. It appears as a vast expanse of sagebrush and shadscale, but playas and washes connect to interesting features of incised hills and mountain fronts. We move up into the foothills to explore a possible camp in the vicinity of the historic-era Kaiser Mine.

The ground remains saturated from recent snowmelt, forcing us to avoid mud gullies and soft spots at the road margins. We back out of the mine area to find some flat ground at a trough with an old rail tanker-car as a water tank. The trough holds good water, but there are no signs of recent use. We will only be here overnight and water is easy to come by this time of season so we aren’t in long-term conflict with any critters that might rely on this water source.

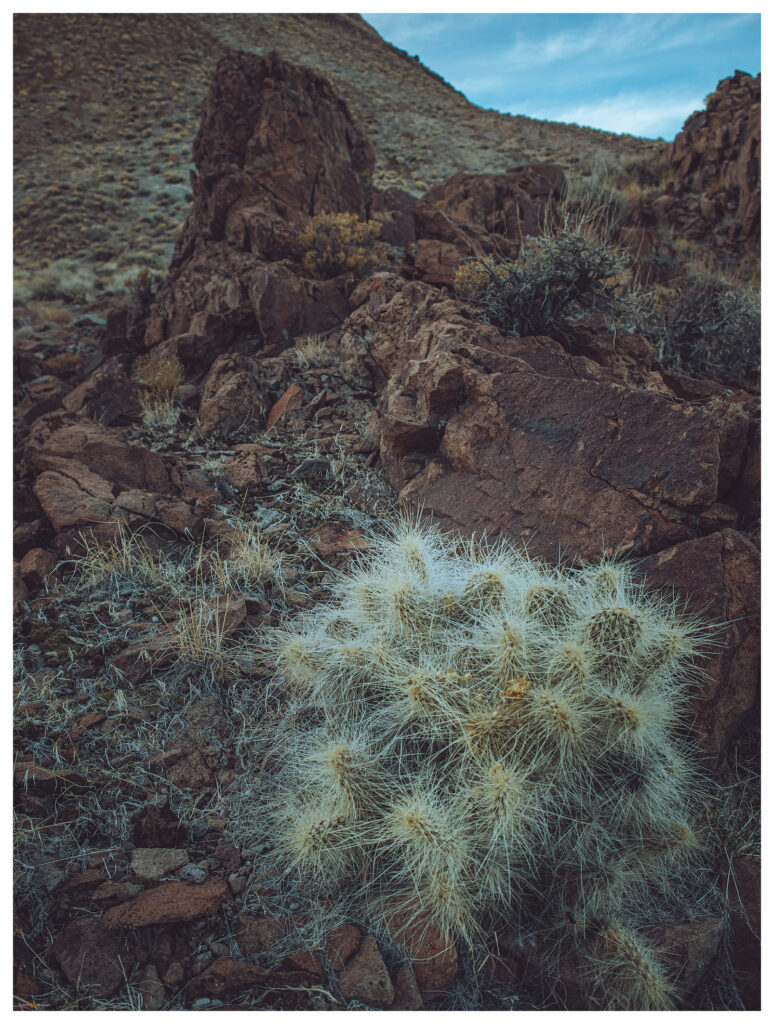

We set camp quickly and engage the truck to climb along two-tracks south of our camp at the Kaiser Mine road. A muddy two-track takes us to a start-point that is gives us a three-mile hike to the summit of Mount Anna. Our route contours generally along a prominent contact between uplifted volcanic flows and ashy tuffs. A light-colored, fine-grained deposits suggests the once inter-bedded mud of a caldera-filling lake. The ground is damp but we avoid the ‘gravity-dirt’ that clings to boots and inhibits progress.

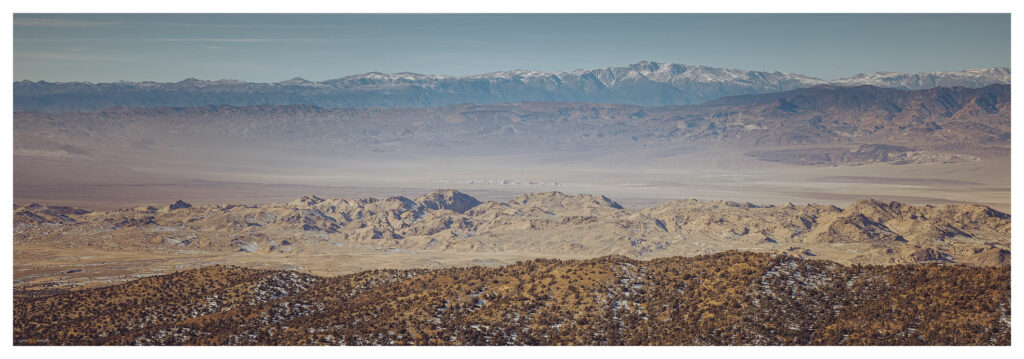

The sunny afternoon is perfect — calm and somewhat warm. We cover ground quickly to find some fantastic volcanic canyons and dry falls in the wash below the summit. Although we’ve walked a couple miles, we really haven’t gained any elevation and the mile or so of the final push is nicely steep, with great, expansive views to the east and south. Arc Dome rises in the Toiyabes, a goal for the very near future.

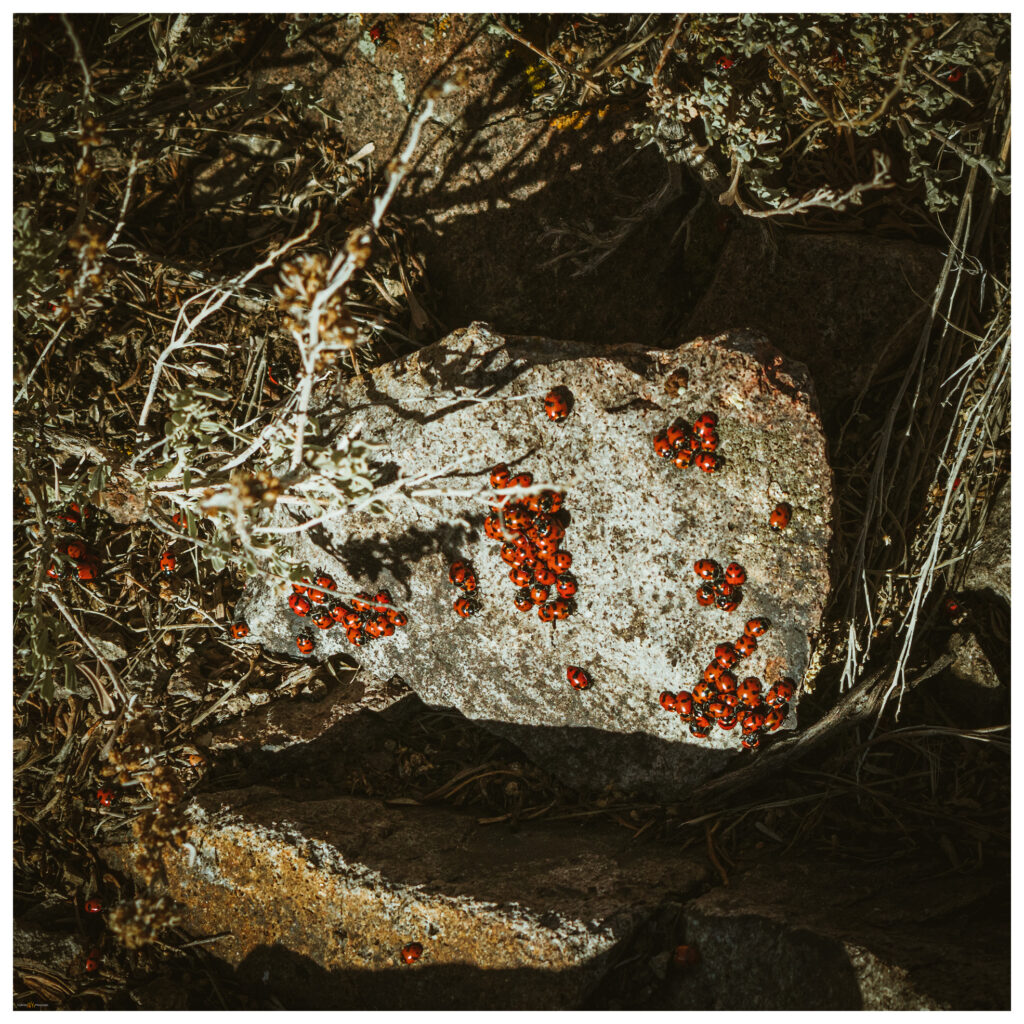

Darren reaches the summit to find well-constructed platforms of concrete and gravel. These are likely footings for military tracking stations or, possibly, for seismic measurements. There are no clues otherwise. I follow just behind him, suprised that the summit is altered but finding the views exceptional under still clear skies. And we are not alone. An aggregation of lady bugs (Hippodamia convergens), a relatively common sight on spring-time summits, brings the rocks and low sage of the summit outcrops colorfully alive. It takes some care to not step on the swarming orange beetle blobs.

We trek downward, retracing our cross-country routes and exploring the features of conglomerate washes and localized debris flows where linear levees of cobbles swarm along steep gullies and rills in the mountain side. We are back at camp after sunset.

The night remains calm as we ponder our target for tomorrow — maybe the low set of hills on the opposite side of the valley. But the rain starts just after we climb in for the night, and soon the near silence of snow begins to transform our surroundings. The wind never came, but we wake to a blanket of snow with a cover of wispy fog. The damp brings a chill absent until we start packing up. Another climb is out of the question, but we can traverse to East Gate and explore the cleft of Buffalo Canyon. We descend the Kaiser road slowly, with truck and trailer giving easy traction in the fresh, wet snow. We eventually leave the snow cover momentarily at Middlegate but it returns with depth in the canyon above Eastgate.

We venture in and Darren soon notices a group of bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) high on the cliffs of the canyon’s northern margin. These are a nice gift on a snowy morning. We watch the herd for a while and explore a series of waterfalls that only exist after a wet storm. The storm comes with a power that seems a purposeful attempt to make up for the calm of the previous night. At times we hit storm bursts that seem like summer storms, but their turbulent winds drive snow mixed with the usual dust and tumbleweeds.

Buffalo Canyon Wildlife Collection

Mt Anna is not a prominent peak, but it gave us the gift of its textured slopes of volcanic rocks and badlands. It led us to a dramatic morning and a visit to the bighorn sheep of Eastgate. Even the small hills lead to big places.

Keep going.

Please respect the natural and cultural resources of our public lands.