I am back in the Mojave. In northern Nevada – in the sagebrush steppe of the Great Basin Desert – the transition to spring has brought a series of atmospheric rivers that vary from warm rains to several inches of new snow. Our water budget appreciates it, and the ski resorts are happy, but it lowers the potential for backcountry travel across the northern tier of the state. But late winter in the Mojave has a very different effect. The precipitation nourishes an ephemeral but amazing green, punctuated by blooms of wildflowers; the typically sharp and prickly landscape softens. Drawn by this ephemeral setting, like last month, I am once again in the Mojave.

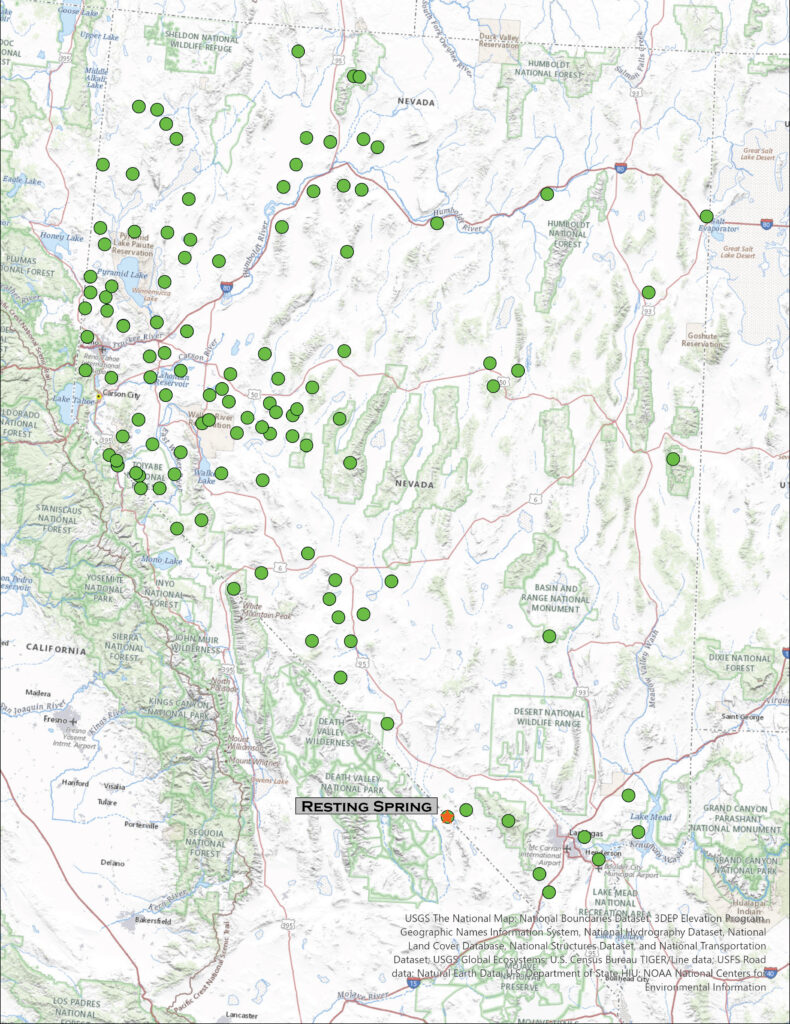

After exploring a few roads on the north side of the Resting Spring Range – most went nowhere or were badly washed out, I set camp on some desert pavement formed on small fans in low, hummocky foothills. The narrow mountain range rises above the Amargosa River with most of its mass in California and only a northern spur and expansive alluvial fans extending into Nevada. My target is the Nevada high point, marked by a small, ridge-line outcrop well below the prominence of Shadow Mountain, the range’s actual summit. I will head up there too.

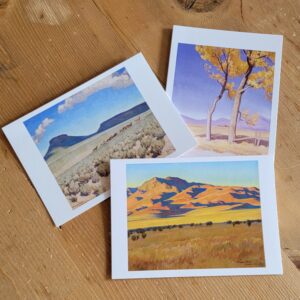

But, first, I will turn the calendar back to yesterday. Desna and I visited the Nevada Museum of Art where there is a wonderful exhibit of Maynard Dixon paintings, poetry, and photographs created during his excursions to northern Nevada and eastern California (open until 7/28/2024). I mention this because first, I really enjoy so much of his work and, second, I think it important to look at art, especially landscape art, and to consider what I like about it. This might provide direction for my landscape photography. Dixon’s use of saturation and contrast, in color and in light, evokes my emotional connection to desert landscapes. His composition is typically minimal, and he has little hesitation in expressing the open sky, dotted with bright clouds, over stark shadows streaking across desert landforms.

Photographers, especially landscape photographers, often cringe at mid-day or high-contrast conditions, preferring the raking, red hues of sunrise and sunset, adding in dark, glowing clouds for dramatic impact. I love these too. I can, however, find challenge and growth in applying a touch of Dixon’s eye, maybe, to my photographic work – both in seeking and exposing compositions and in creative processing, as a painter might. Who knows? I may never be successful, but it got me thinking about its application. Oh, and third, I spent a lovely afternoon with Des.

Back in the Resting Spring Range, after an evening exploring the pavements and hummocks around camp, I am up before first light, making coffee and collecting a few calories before setting out. I need to walk about three miles of alluvial fans before hitting a punchy slope to the Nevada high point. I go by headlamp, cresting a low hill where an almost complete darkness extends in front of me; the yawning space of the vast alluvial fans soaking all light, from the faint light of my headlamp to blackness to a very distant starry horizon. The night still feels close around me. It is a calm silence, until a Burrowing Owl calls from somewhere far ahead and below; her call a lonely reminder of the few critters that call this desert home. Again and then again, a quiet hoot-hoot is the only sound. I walk into the dark.

(Map Point #2)

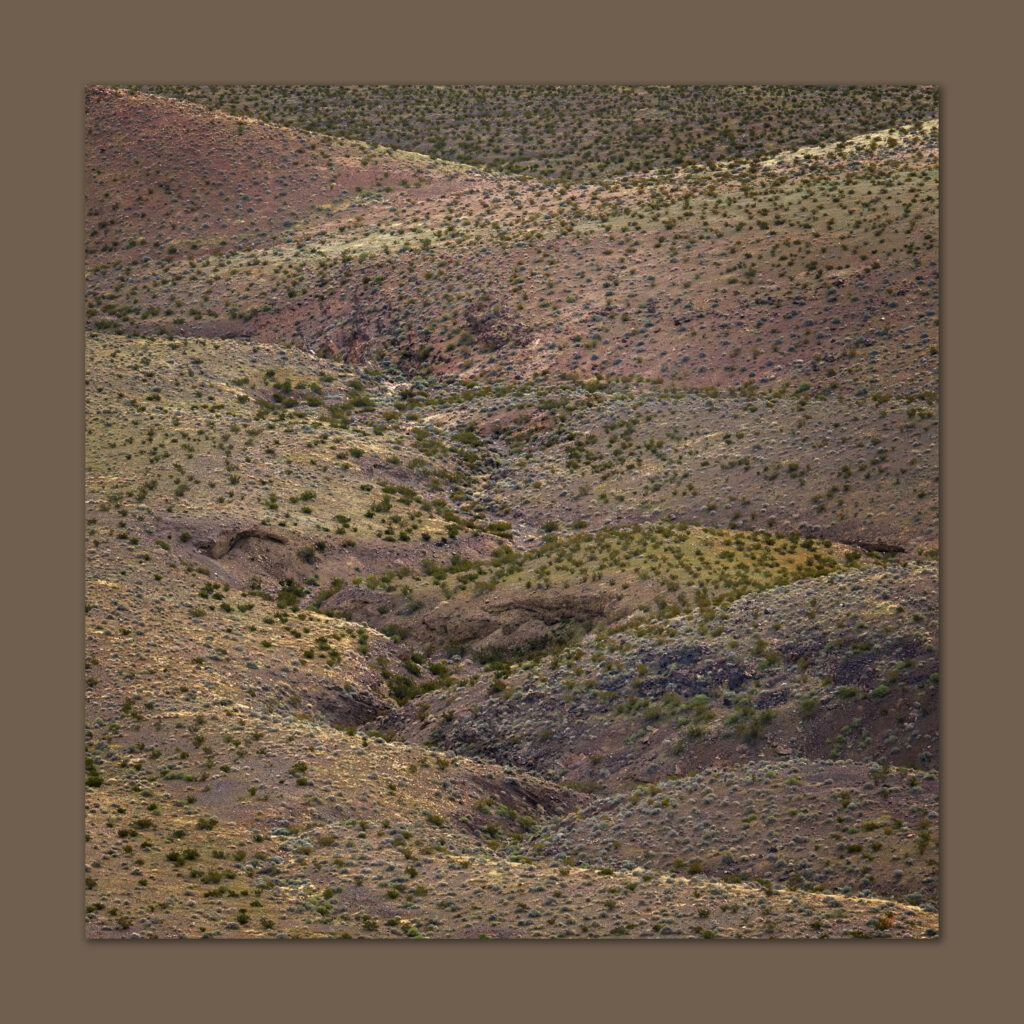

As the light grows, I am in the openness of the fans, moving between desert pavements with dark patination – old, stable fan surfaces – and incised, bouldery washes exposing light-colored alluvium disturbed only recently. The variegated surfaces alternate to reflect the temporal structure of the piedmont or bajada below the steep slopes of Shadow Mountain. A Black-throated Sparrow flits and sings among the creosote and saltbush. The beautiful, sing-song call of a Rock Wren echoes from boulders along rock levees and debris flows that choke the fan’s incised gullies. The morning is perfect. There is a pink in the sky that off-sets the dark fan surface, and newly green blooms of the desert compliment the yellow-brown of the mountain backdrop. Bright yellow highlights reach out from the growing wildflower bloom – Yellow Suncups here; I am early for the ‘super-bloom,’ but it is definitely building.

Rocky, talus-screed slopes lead to the Nevada high point at 3960’ above sea-level; I have climbed just over 1500 feet above my camp. Marked by a cairn on an otherwise non-descript ridge, the highpoint is a great viewpoint, nonetheless. Shadow Mountain looms to the south and Amargosa Valley drops precipitously to the west. The sun has risen behind me, and the wind is picking up. I cross the state border in a crease where the ridge drops from the Nevada side, I then begin a good ridge-walk toward the summit, 1000 feet or so above me.

It is a nice climb with great views in every direction. While the summit of Shadow Mountain does not reach above 5000 feet, the Resting Spring Range remains a prominent landmark visible in all directions. I am happy to be on the summit and realizing I have been looking at this peak for many years, and can now enjoy it from a different perspective – it is always satisfying to be driving or flying, and while looking up (or down) at a lonely spot, knowing that I have visited and experienced it for a short time.

I work my way down, visually mapping the variegated alluvial fans with their shaded pavements of various ages. I can easily identify four surface ages based on the maturity of desert pavement. Dark surfaces with seemingly uniform pattern of rocks, some that fit together like gravelly puzzle pieces, are generally old. Very old; it takes hundreds of thousands of years for the weathering to create the distinct, intricate patterning. Younger surfaces will be lighter colored, with rougher surfaces, seemingly random rock patterning, and even evidence of recent flooding. And several intervening surfaces along a continuum of very old to, well, practically yesterday. From a distance, the patterns can be clear, and I often map landform age based on aerial imagery that resolves the temporal relationships nicely.

This is important because archaeological sites, their age and preservation, may be patterned in close relationship that age of a landform or its surface. Sites of any age may occupy the oldest pavements – let us assume there is some clustering of plant, animal, or water resources that might have led people to this location. Because that armored surface is as stable as it is old, it is very unlikely to hold buried archaeology. So, the information you get from the distribution of artifacts on the surface is the only information you are going to get.

As we move to surfaces that have formed and stabilized in the Holocene (say, the last 12,000 years or so), we may start to see some patterning among the surfaces, with some interesting changes over time; the relative age of fan surfaces may provide the first clues in looking for such patterning. Very young fans (with evident debris flows and tumbled cobbles and boulders) suggest that most sites may have been wiped out, and while you may find some displaced artifacts, there is little detailed information in such a disturbed setting. The patterns can shift rapidly as one moves across such an ancient and complex fan.

I recognized four temporal surfaces on the bajada (i.e., coalesced fans) expanding from the canyons on the northeastern side of the Resting Spring Range. On the map, Qa1 highlights the oldest surface, marked by darkly patinated and strongly developed pavement. Younger fans cut through the Qa1, leaving its ancient surface abandoned to continued slow, constant weathering. The gradient of surfaces from Qa2 to Qa4 reflects younger landforms and a general increase in recent erosion and/or deposition. The Qa4 is where the occasional floods happen or have happened relatively recently; one can hardly predict the next flooding disturbance to spread across the fans as the flashy flows find their paths basinward. A spot may be stable for centuries, until it is not.

As usual, I focus on the younger landforms (not rocks) and the processes that build the environments and habitats of today – that is why my maps only highlight the young, active landforms. The older rocks, their structure, composition, etc., play a role, but I want to document and understand the work that wind and water can do now that the mountains and hills are in their place, at the scale of the Holocene, at least. That is geomorphology, in a nutshell.

I reach camp happily after seven or so hours of walking out and back. It was a special and relaxing day. Unlike last month in the Last Change Range, I was well-provisioned, and my gear worked flawlessly (I did film more than I anticipated, and I should have brought my better audio set-up – the wind noise in my YouTube post embarrasses me). Although it is often better to focus on one activity during an excursion – Am I here to climb, do photography, map landforms, or make geomorphology videos? – I took the time, this time, to do a bit of everything during my walk. It is good to get a complete outing like this occasionally. This was a great one.

I continue this journey, after packing up my little camp, with a photographic excursion into Death Valley, and then on to more focused fieldwork in the landforms of the ancient Mojave River further south. It has begun well.

Keep going.

Please respect the natural and cultural resources of our public lands.

Leave a Reply