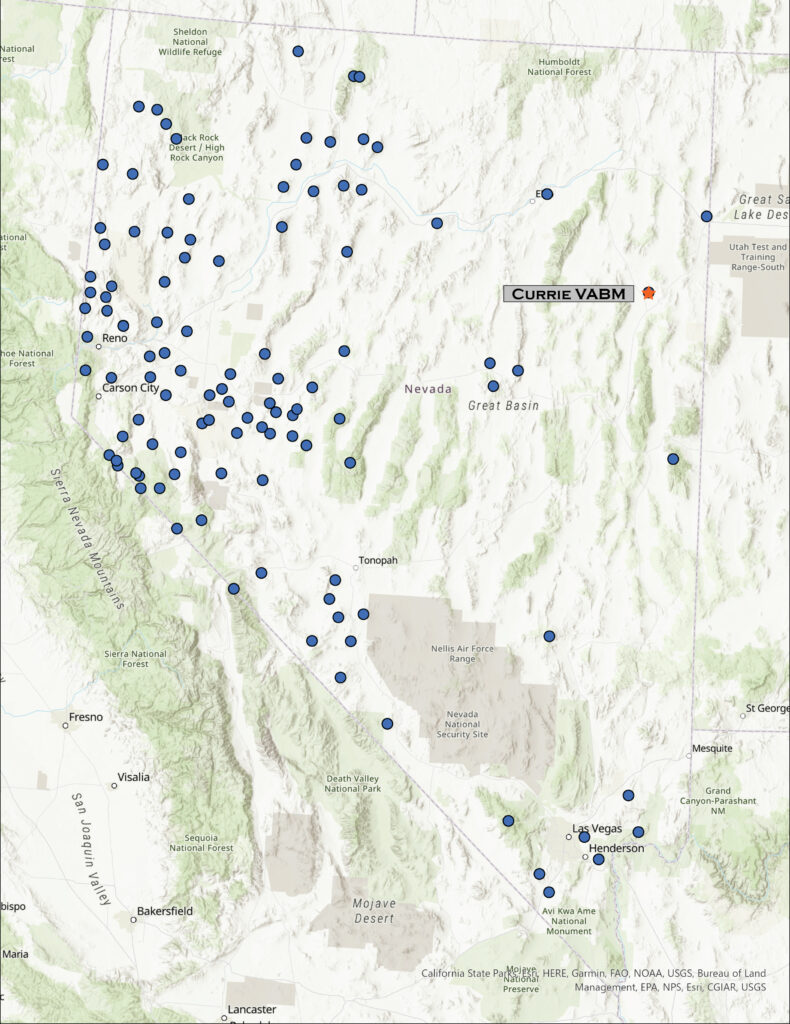

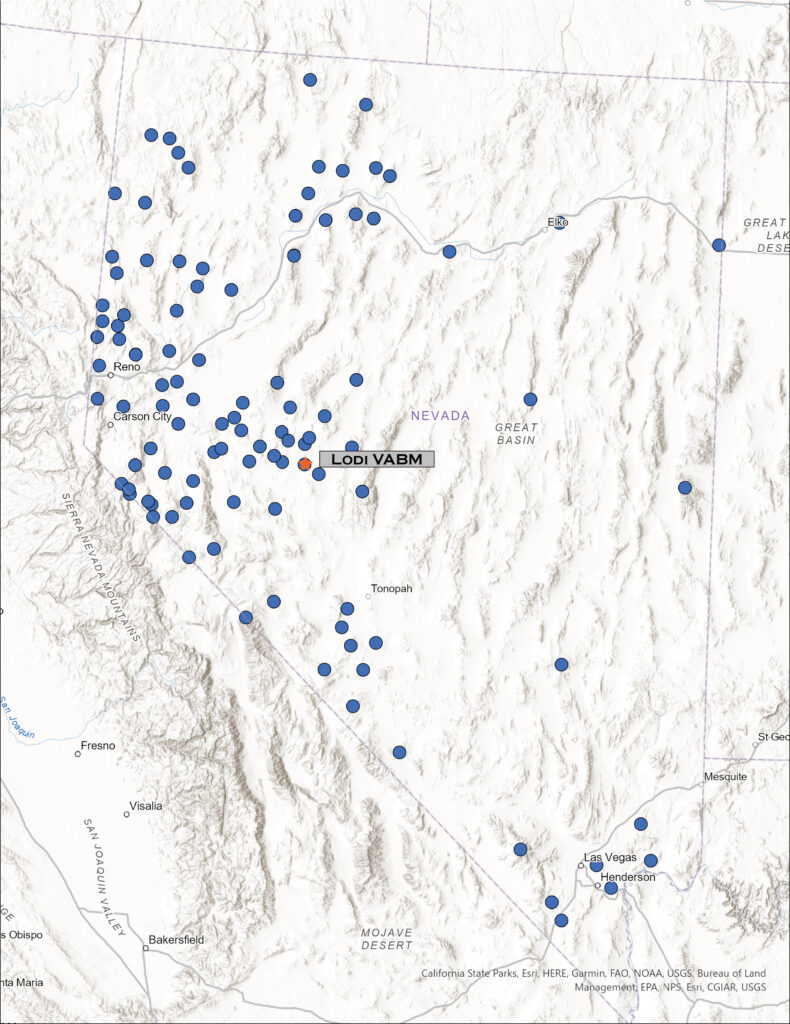

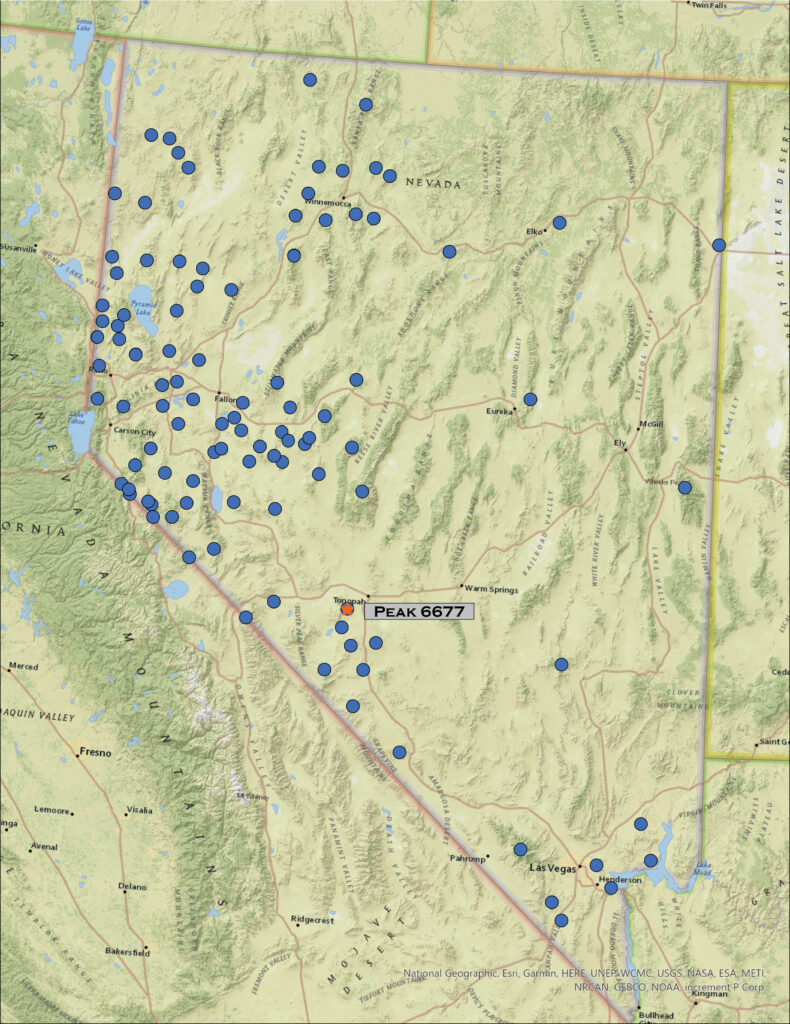

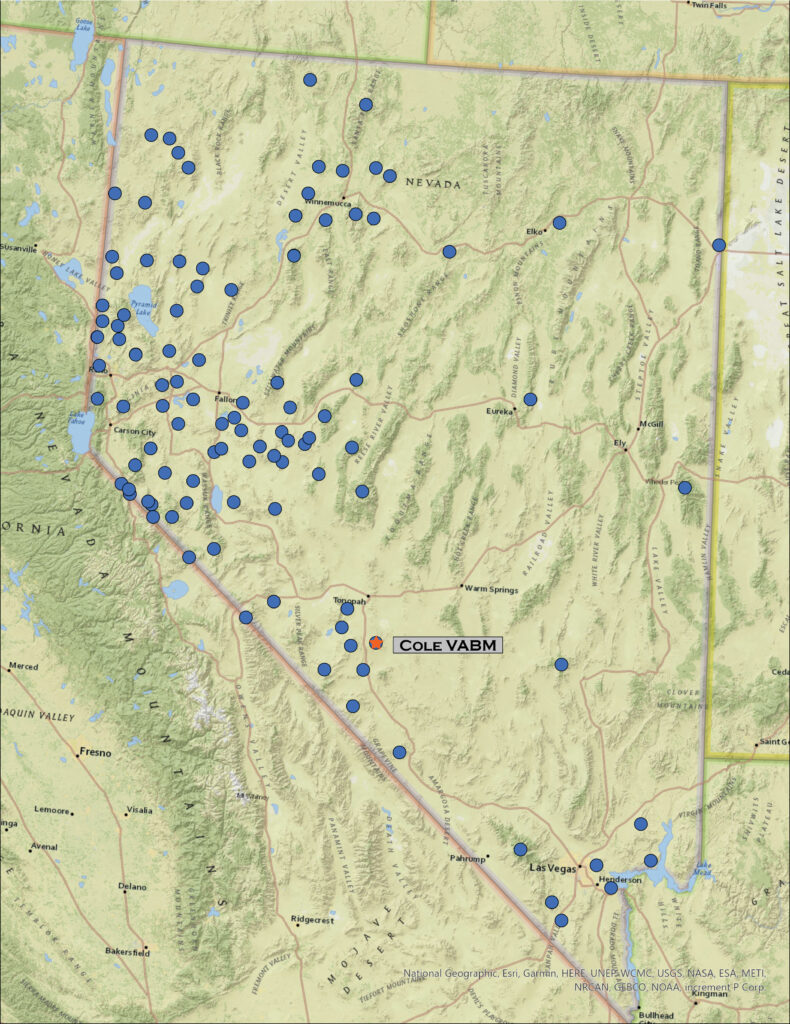

I was on my way to the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah, to join a couple colleagues for fieldwork across the Bonneville Basin, choosing a traverse of Hwy 50 as my preferred and typical route. With days getting to summertime length, however, I had time for a diversion. The Currie Hills rise easily about halfway on a south-to-north line between Ely, Nevada, and Wendover, Utah; I was due for a high point.

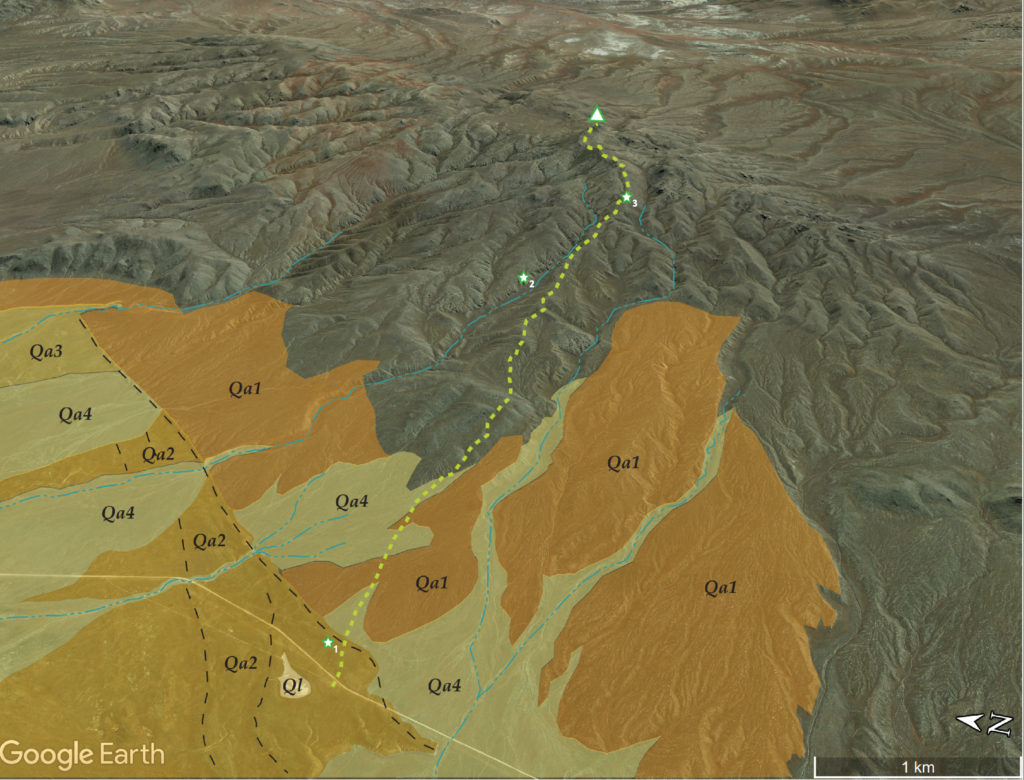

A tight, barbed-wire gate, immediately adjacent to the White Pine-Elko county line, marked a good two-track road heading across a northern embayment of Steptoe Valley, the Currie Hills a few miles distant. I explored a few turns and detours before parking on a broad fan opening from the southeastern front of the hills.

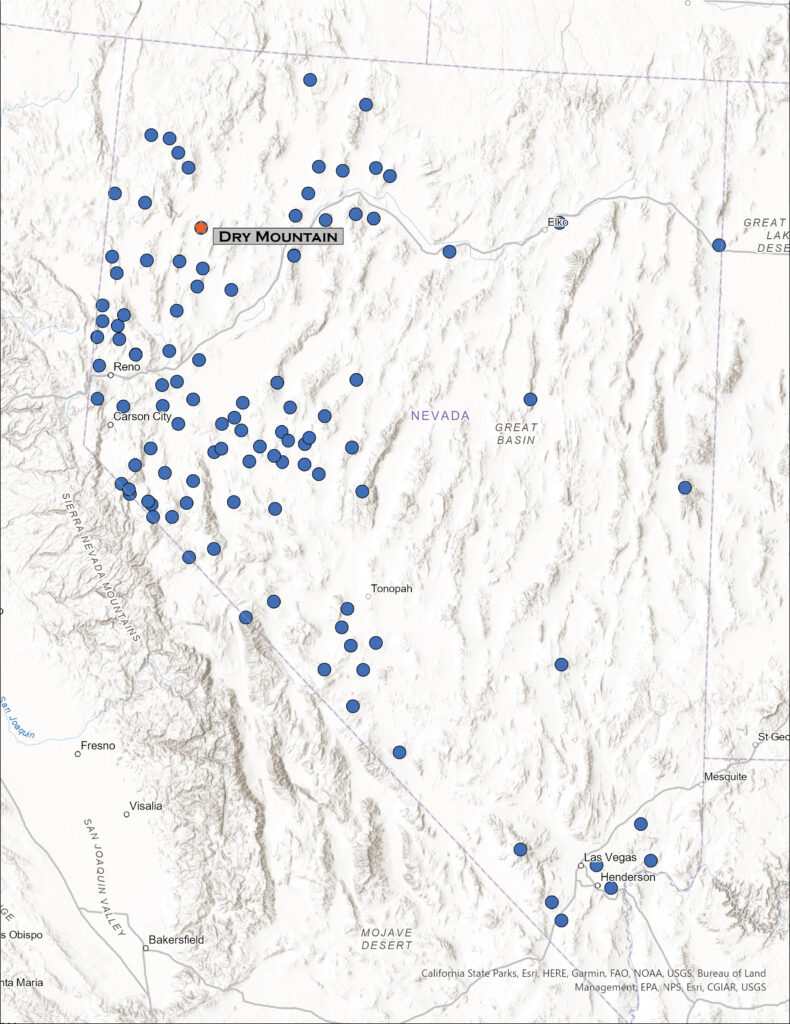

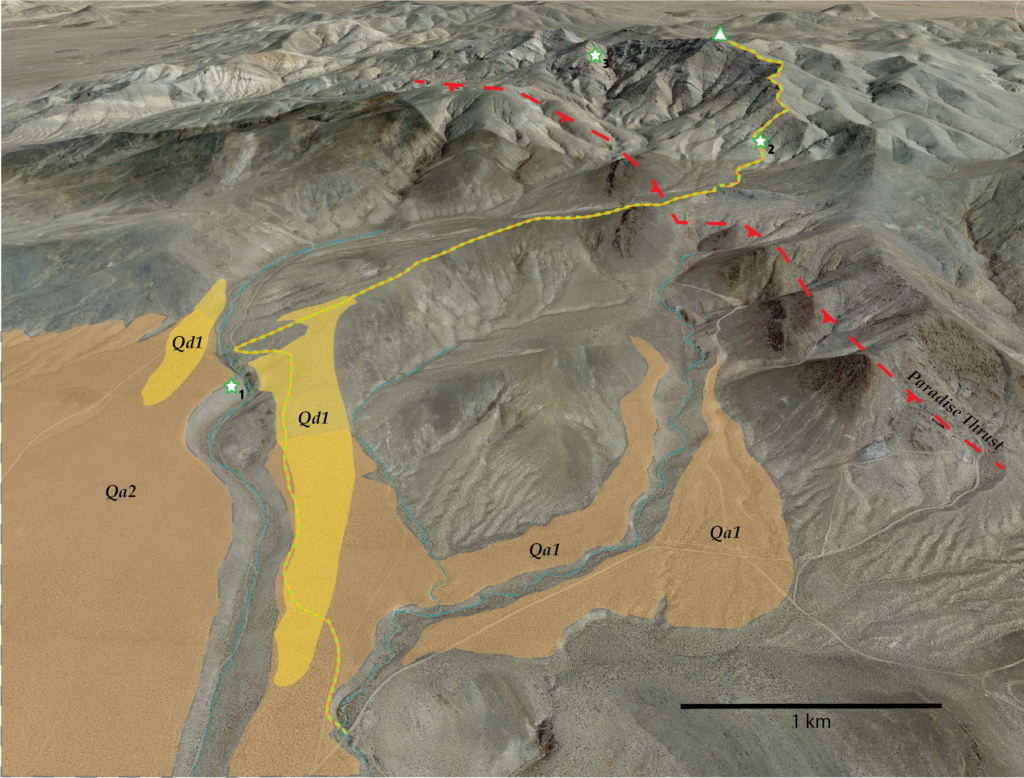

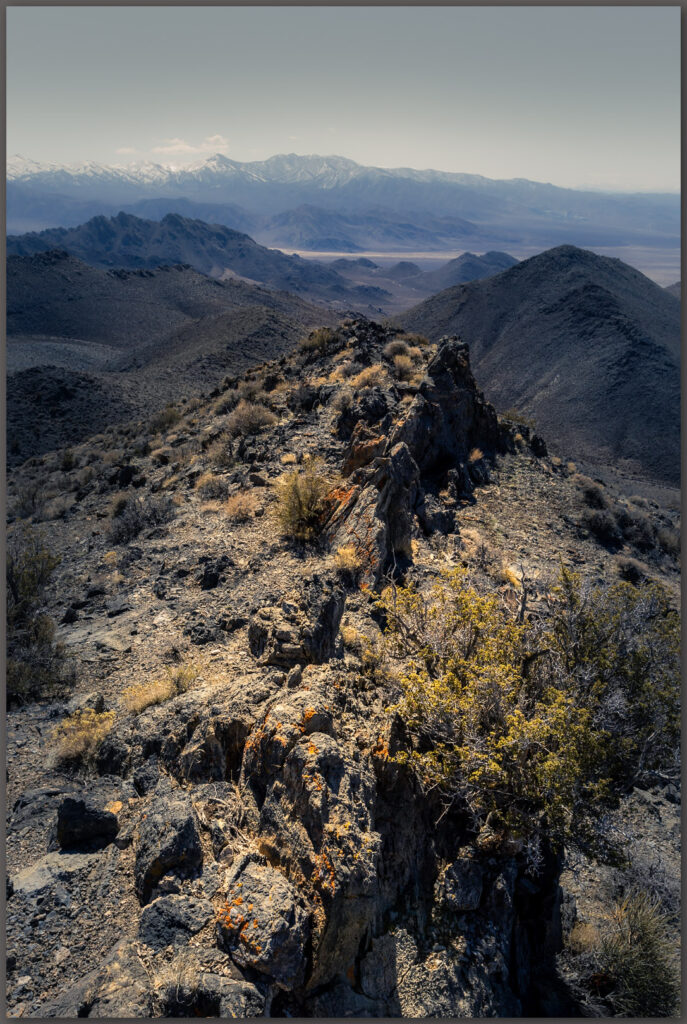

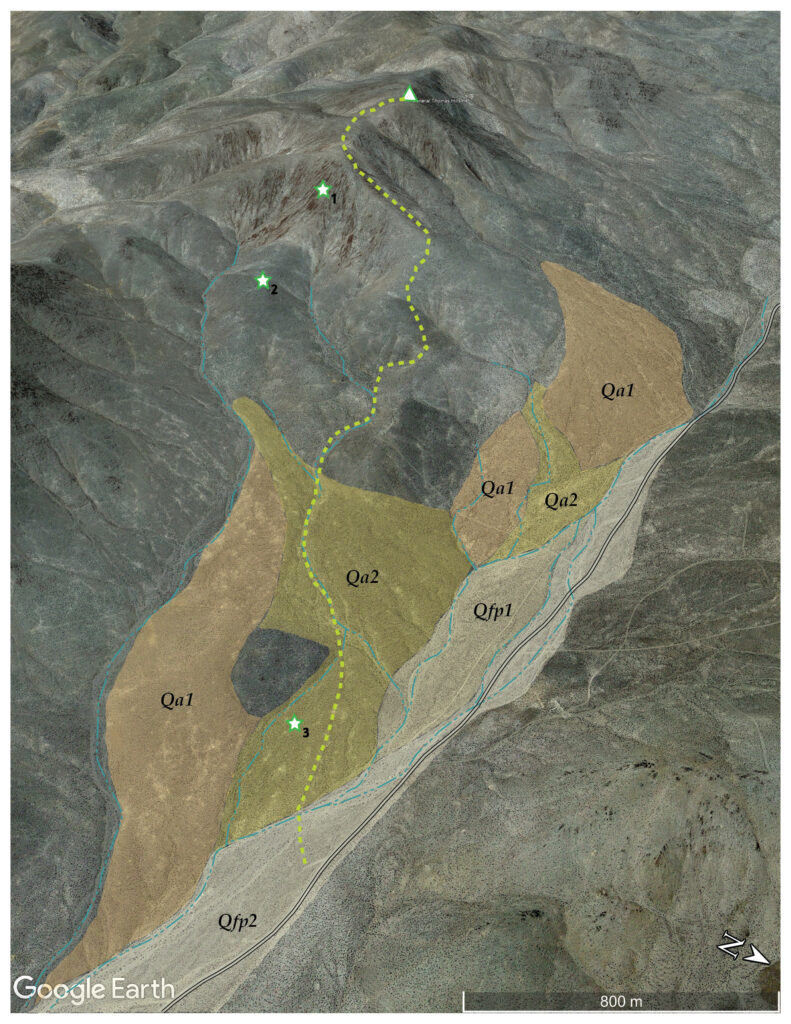

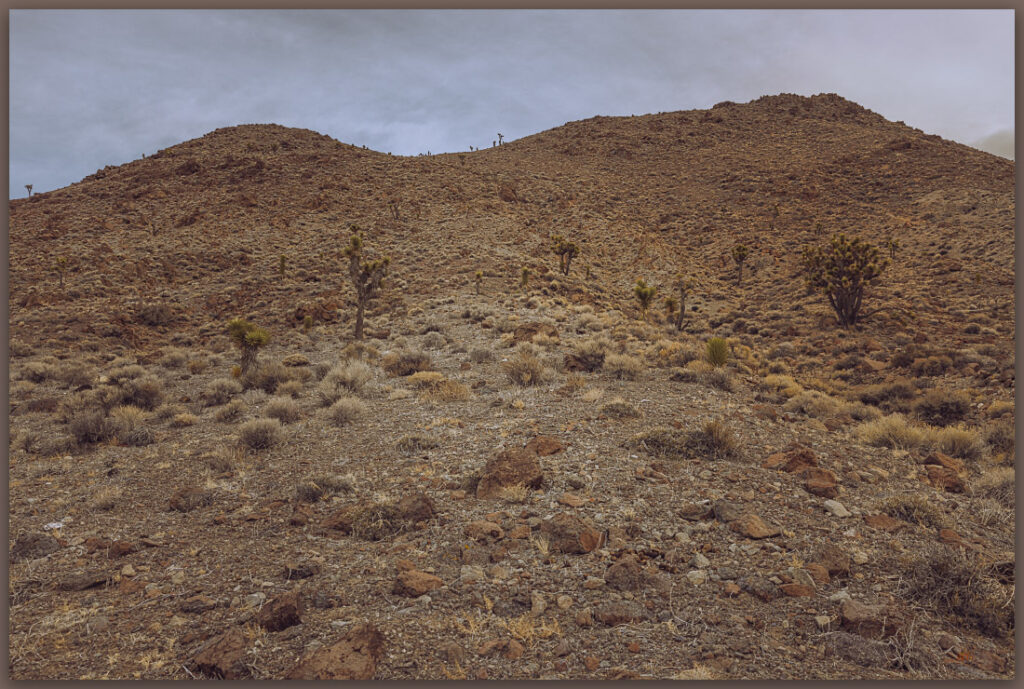

The Currie Hills are low, rounded hills whose eastern side is volcanic rocks overlying red-hued sedimentary rocks, generally old fans (Qa1) extend from mountain-front with small inset drainages (Qa2) leading to dusty distal fans several mile downslope, where loessic alluvium chokes the low-lying axial drainages leading to Goshute Lake in the Steptoe Basin. I traverse moderately angled slopes, transitioning from volcanic colluvium to weathered tuffs and back to steep colluvium rolling from the summits. There is a nice pinyon-juniper woodland, though some of the pinyons are suffering from drought and reduced ability to fight off beetle attacks, but others a healthy and productive.

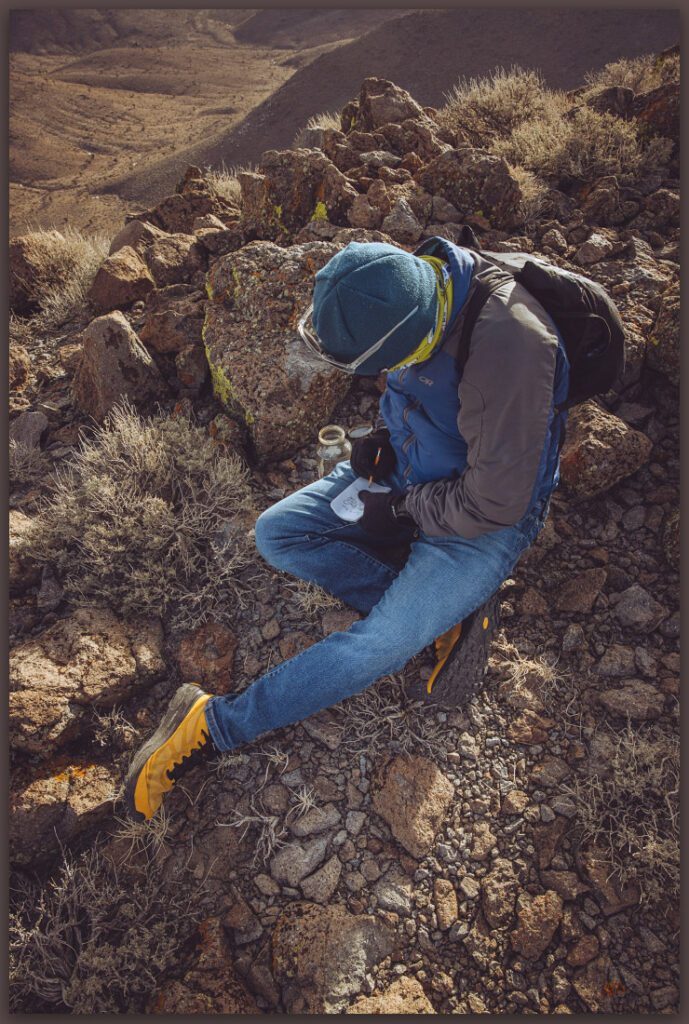

I find one false summit that points me toward another swale from which I can see the summit cairn prominent at the high point. What was once a blustery day dotted with fast-moving squalls has opened up nicely. I follow a similar path downward, shifting slightly to wander through some of the younger alluvium where the sagebrush grows deeper. Here I find a Lark Sparrow and then a Gray Gnatcatcher. The former watches proudly from a juniper while the latter flits in the brush, basically ignoring me. I am soon back at the truck for the dusty drive out. I drive into the evening to eventually reach Salt Lake City.

These small, unobtrusive ranges do not call out from the highway; their summits low, rounded, and often draped in woodland or sage. Yet, the walks never cease to bring pleasure along with unique sights and just a bit more experience traversing the variety of landforms that comprise the Great Basin landscape. I was also rewarded with ab addition to my ‘life list’; the Gnatcatcher was a new one to me. Once again, a small mountain range provides a wonderful quick diversion from a long day’s drive.

Keep going.

Please respect the natural and cultural resources of our public lands.