It took me awhile to escape Fallon, Nevada, where I attended a conference hosted by the Nevada Archaeological Association, congratulating a colleague on receiving the Silver Trowel, recognition of a career devoted to archaeology in Nevada. From the confines of the meeting rooms, I retreated, none too soon, to the splendid loneliness of a nighttime highway into the Black Rock Desert. I drove for maybe two hours.

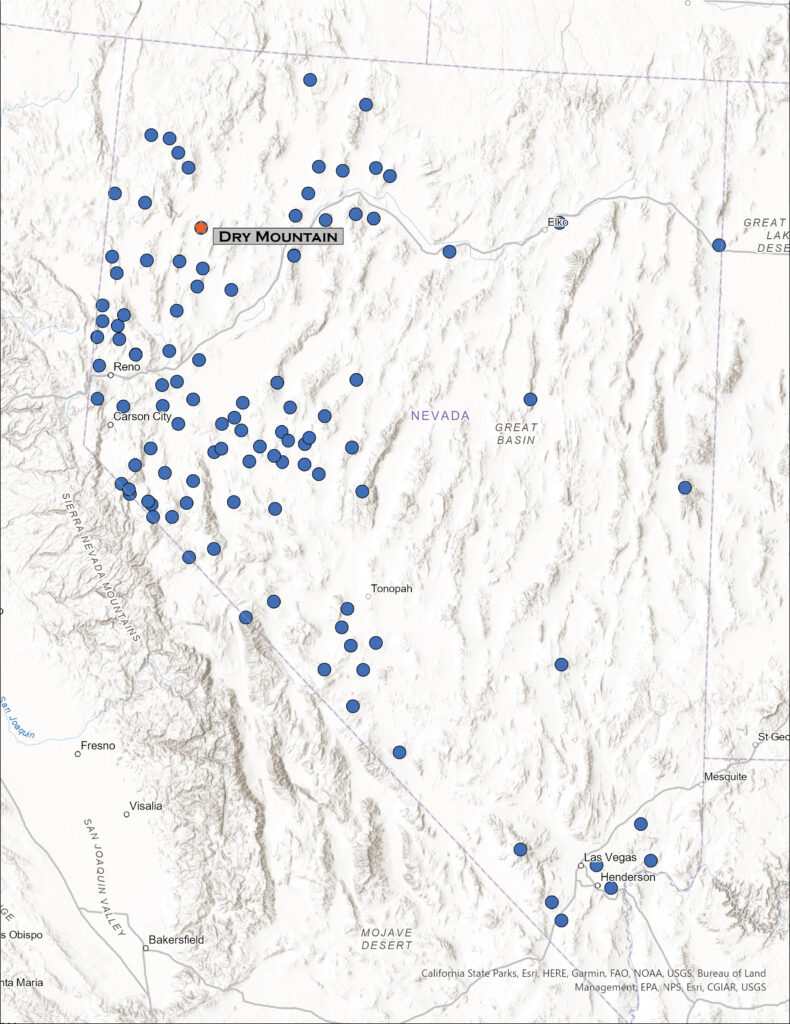

At the ‘high road’, our colloquial name for the washboard dirt highway connecting, sort of, Gerlach and Winnemucca, I traverse the southern margin of the Black Rock playa in the dark. I am headed toward the Pahsupp Mountains, where a prominent block rises above Trego Hot Springs at the playa margin, but the range’s high point is stretched out to the south as Dry Mountain (6,526’). As I turn away from the playa, the usual landmarks having long faded into the night, my view is confined to flashy, narrow strips of rabbitbrush bright at the dusty road margins. A jackrabbit darts through the high beams on occasion; hard to tell, but I don’t think it’s the same one each time.

I had scouted on googleland earlier, marking a possible camp in my GPS. The waypoint appears my dashboard screen, finally, and I pull off the road. Not a camp you would write much about, just a wide spot where a two-track takes off from the main dirt. I will not see another car until I am back on the highway tomorrow, so once I climb into my tent, I can immediately forget that I am basically camped adjacent to an intersection. No traffic here.

There is a chill in the air, and wispy high clouds resolve as the white-gray of the morning sky shifts to blue. Dry Mountain leans back into the sun toward the eastern horizon. I have five miles to walk to the high point – up a long, generally smooth ramp of alluvial fans and beveled pediments to reach the rocky summit.

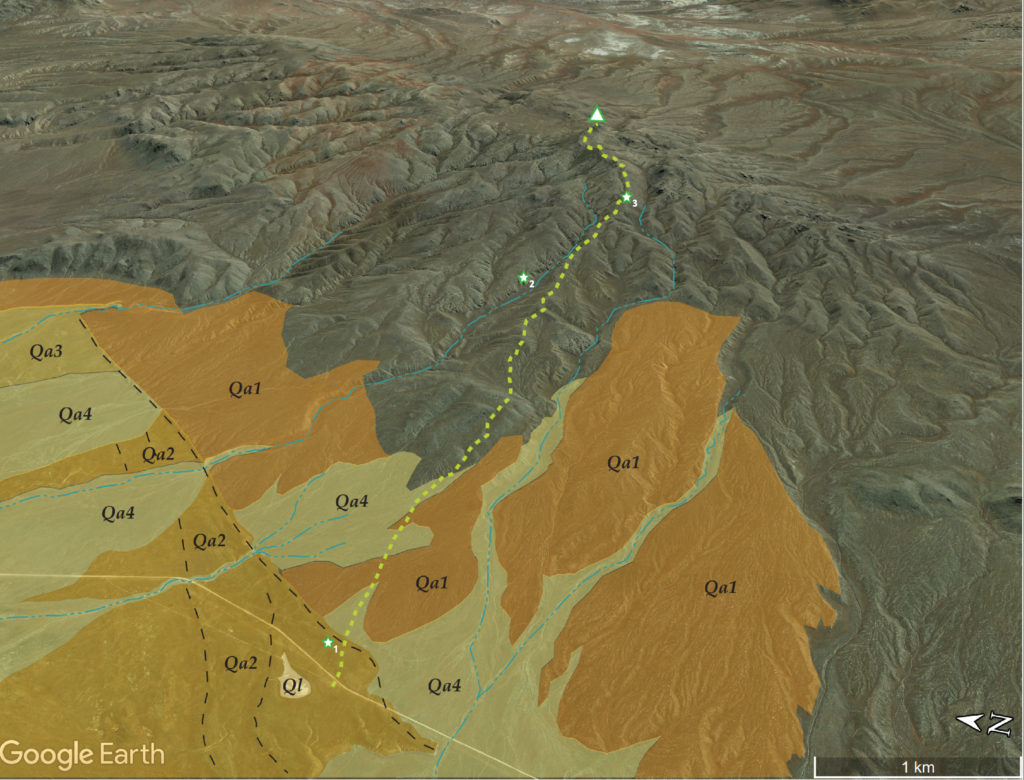

I first traverse a set of alluvial fans where pluvial Lake Lahontan built gravel berms and beaches about 15,000 years ago. The remnant strandlines show as subtle, rounded mounds of dusty gravel stretching perpendicular to the gradual slope of the mountain-front fans. The uppermost strand cuts into the slope formed by a Pleistocene-age fan (Qa1 – older than the lake stand at 15,000 years ago), its erosional scarp formed as waves cut into the gradual slope and arranged gravel in the mounds we walk across today – it is easy to see this berm and scarp tracing its way north and south on aerial imagery just above the road. As the lakes receded, they left stringers of other off-shore bars and recessional beaches, while new alluvial fans (Qa2 and Qa3) chased the receding lake basinward. Once the lake had faded – and during its long, current absence through the Holocene (since 12,200 years ago), young alluvium (Qa4) flows in drainages; it is sometimes dammed by the older berms, coalescing at gaps where storm floods formed cuts in the berms or, in other places, it buries the former beaches altogether.

I continue up the long ramp to gain the beveled slope of the granitic pediment that abuts craggy peaks nearer the summit – I’m about halfway through the gradual climb. I can look across the deeper canyons and see how the top of very old (millions of years), uplifted granite, with a fabric of nearly vertical structure, is cut and capped by a gently sloping veneer of alluvium. If I was walking across that alluvium, I might think I was on just another alluvial fan, but the sandy to cobbly veneer is thin (maybe a few meters) and the landform, as a whole, is bedrock – so we emphasize the big picture and call it a pediment, though as archaeologists we would want to be aware of the age of the alluvial veneer. Here, it is generally active and young – it is subject to common slopewash and shows very little soil development. The alluvium is Holocene; there is a lot of time missing from this generally erosional surface. This is the landform that feeds the fans below.

But onward.

I gain the steeper sections of ridges and eventually work my way past one false summit to the bouldery crags that form the steep outcrop of the Dry Mountain high point. The views in every direction are Basin and Range at its best. There is shallow lake moving across the Black Rock playa at the terminal end of the Quinn River. Dust is rising from the Smoke Creek Desert to the west, and I can sense a change in the freshening breeze; it will be gusty soon. It is time to settle into the long walk down to camp.

Although I cannot help delving into the pattern of landforms as I wander to any high point, I always hope to show the hard, subtle beauty of the Great Basin Desert in a series of landscape photos that go beyond the mapping of geology and geomorphology. To me, these things are inseparable. But bringing the desert to life under blue-sky, dry days is difficult, especially when a long walk means I don’t have time to look for smaller scenes – before each walk, I fantasize that some drama will unfold in front of me. On most days, however, a quiet, desert walk misses the drama of a gathering storm or the bursting gallop of a pronghorn herd – or hassled traffic and the workaday office, and I disappear into the fabric of the landforms that spread from the mountains where I wander. Portfolio pictures may come another time.

Keep going…

Please respect the natural and cultural resources of our public lands.

Thanks for the trip, it’s like I was there.

Hoping some day soon you can be (well, on another high point for sure).

Been maybe 12 years ago we followed horse trails on and around dry mountain on mountain bikes, followed by a soak in Trego hot spring.

That’s the way to do it!