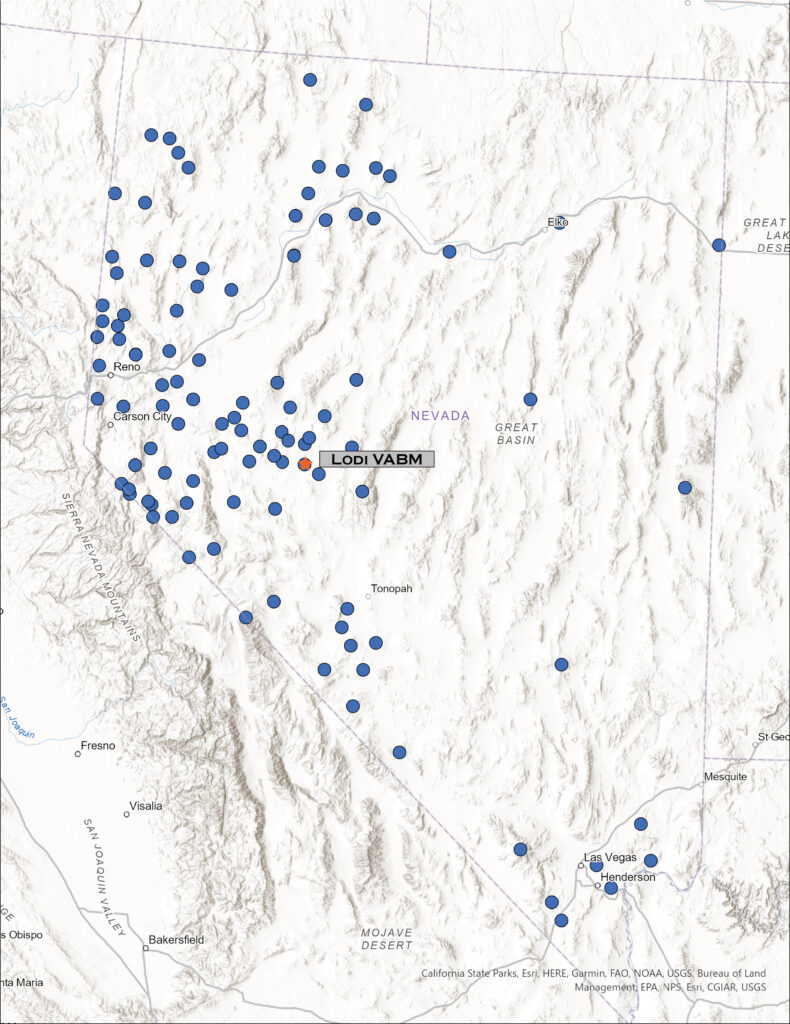

Occasionally, a highpoint excursion takes me into an area where our field teams are working, and this provides a good opportunity for a closer look at the landscape surrounding our project efforts. I left home early thinking I would get to the base of the Lodi Hills – my highpoint target on the day – to cover the relatively short, easy walk above Gabbs Valley in west-central Nevada; afterward I might check in with the crews to see how things are going.

In Lahontan Valley, near Fallon Naval Air Station, I came across a well-established rookery of Great Blue Herons, waking up to morning light as the first jets rumble away from the runways nearby. There is some courtship going on, while others are already nested up and awaiting an early brood.

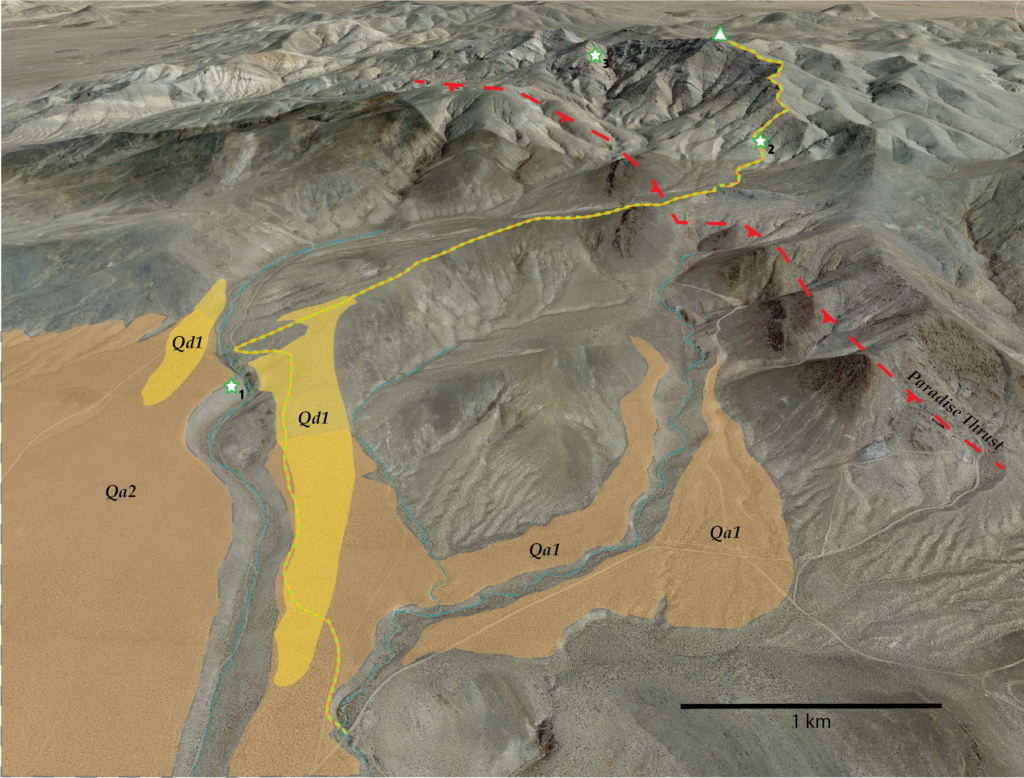

I ventured southward into Gabbs Valley, turning east on the broad alluvial fan that emanates from the Lodi Hills. A good dirt road took me to the base of a shallow canyon below Victory Mine, where prospects and other mining-works mark the hillslopes to the east. I left the rig to walk a two-track road northward, climbing gradually along a sand-covered fan (Qa1). The ramping sand thickens to a sand sheet (Qd1) that has formed on the leeward side of an incised gully that cuts deeply into the fan. The gully exposes a planar surface where the alluvium (Qa2) rests on an underlying, beveled surface of volcanic bedrock, the foundation of the west-facing slopes of the Lodi Hills. The exposure of the canyon wall is a nice example of how proximal fans form on older surfaces along the mountain front.

I turned eastward to climb a broad, sand-covered slope. It is difficult to map these landforms. It is your basic hillslope supported by the ancient bedrock of this segment of the Lodi Hills. So we could map it as dolomite or limestone hillslope (geologists show this on their maps), but the sand sheet (Qd1) is prominent in places, protected behind low outcrops and falling along the leeward side of deeper gullies leading to a broad canyon. I am not overly interested in the bedrock structures, though I enjoy walking through them. I focus on recent, or Holocene-age, landforms generally, so I tend to highlight the younger sand, wondering about its origin and overall mobility. As I move upward and eastward I come to what I think is evidence of the Paradise Thrust fault where older Triassic limestone has pushed eastward and up over younger, Jurassic limestones. The rock units change color, and a few areas so more conglomerate, old debris flows where rock clasts are cemented together, unlike the nearby smooth and fine-textured remnants of older ocean beds. But the thrust change could be further west, I am just not sure about this bedrock, the limestones are so similar.

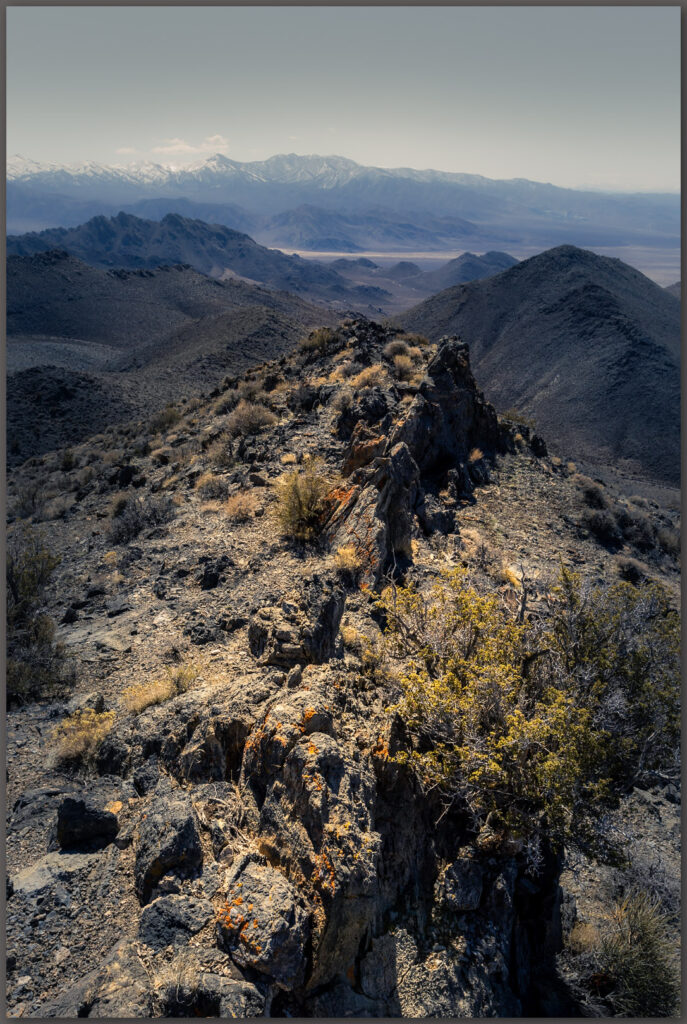

I find some prospects where the slope steepens into a summit ridge. I had avoided hiking the two-track road to the prospects in favor of the nearby ridgeline. These historic-era features are interesting, but I need to keep moving. I climbed upward to the ridge where the rocks get interesting, even in a range as isolated as the Lodi Hills. I could see the tilted and lifted bedrock forming the foundation of the summit and enjoyed the wandering ridgeline until I finally reached the summit.

I watched a small herd of deer wandering the steep-sided gullies below the summit. I do not think they ever saw me. The summit is a cluster of bounders with a generous view in every direction – a worthwhile effort in the relatively low hills.

I did not have much time to linger as I was still looking to meet our crew in the valley below. Nevertheless, I took my time, wandering a more southerly set of ridges and slopes to find another sand-filled gully to reach the truck. Glad to spend a day in the hills once again.

Keep going.

Please respect the natural and cultural resources of our public lands.

Leave a Reply