Cuprite Hills HP (Peak 6071)

6071 ft (1850 m) — 1503 ft gain

2021.03.10

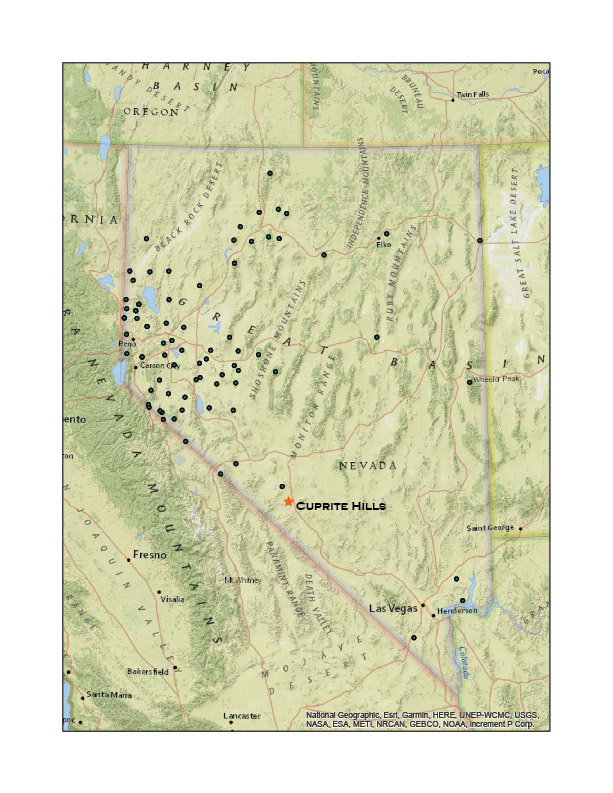

When I first imagined a quest of climbing to the high point of each of Nevada’s named mountain ranges, as I studied my collection of topographic maps, it came as a solution to a problem. As a relatively new student of geoarchaeology, I wanted to experience the variety of landforms, eco-systems, and places in the outback of the Great Basin. How best to do this? I did not want to focus on the well-known, recreational hot spots or prominent, obvious peaks – if only to satisfy my occasional mountaineering urges. So, the quest was born; its goal not simply to conquer mountains large and small but to get out and visit the widest variety of terrain across Nevada, the epitome of Great Basin variability. I have managed to stay on the quest, in fits and starts, for over 25 years. I have recently returned to the journey in earnest, reaching high point #80 – a rather poor average of three a year, I admit – in the Cuprite Hills.

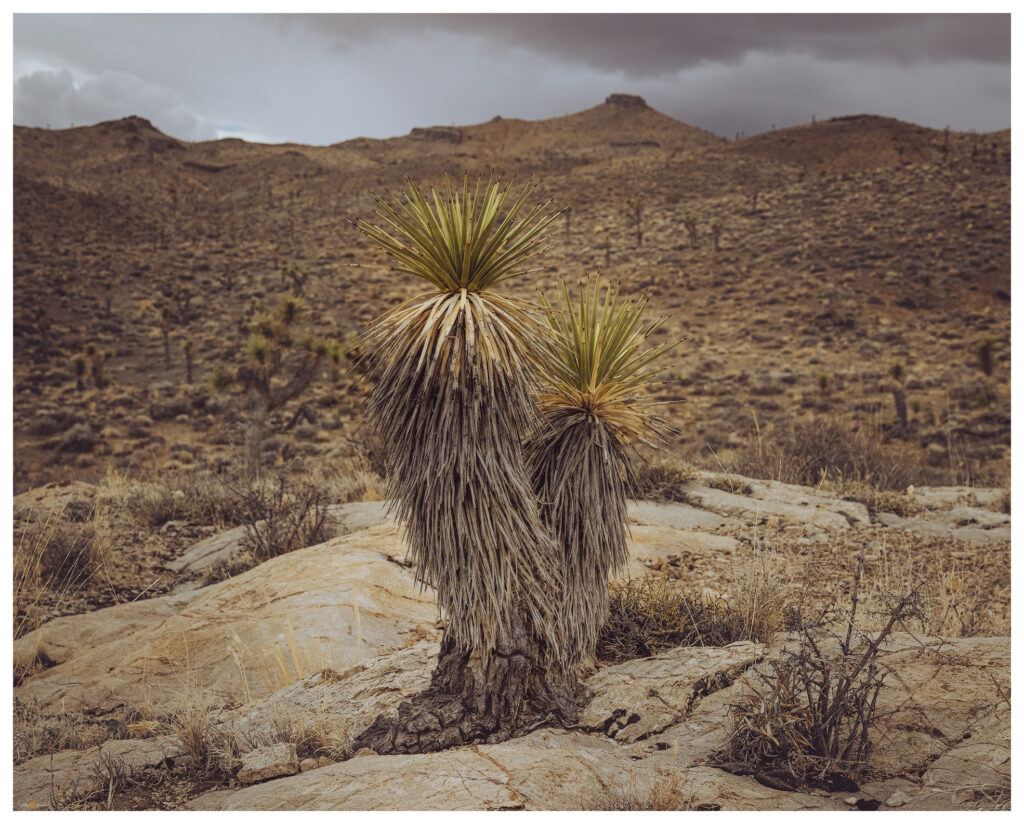

I had a field project mapping alluvial fans along the Gila Mountains near Yuma, Arizona, and that required a drive south on Highway 95 to Las Vegas and beyond. I checked my list and consulted my geographic database to see the Cuprite Hills standing lonely along my route. A hike into the dry hills would make a nice break from the day’s drive. Fortunately, the weather forecast called for stormy conditions with snow at elevation and scattered showers throughout the day – I prefer this to an unbearably clear blue sky when traversing the desert. The forecast was spot-on as I left the Walker River to climb into the landscape where the Great Basin eco-system (not necessarily congruent with the area of internal drainage defining the ‘hydrographic’ Great Basin) transitions to the warmer, drier Mojave Desert. The change becomes apparent south of the mining town of Tonopah with the appearance of iconic Joshua trees (Yucca brevifolia).

Dropping out of the Goldfield Hills, dramatic squalls intersect the highway and I am soon immersed in a rampaging graupel down-burst. Wipers on full throttle did little to improve the visibility, and nothing could compete with the sound of the pelletized snow pummeling the windshield. And here, at Lida Junction, I needed to turn onto a desert two-track to find my ‘trailhead’, an arbitrary dirt intersection on the alluvial fan somewhere beyond the squall. The graupel-depth could be measured in inches as I dropped into 4×4 and slowly worked my way up-fan. A coyote stared at me at a fenceline, his posture clearly showing his frustration with the incessant downpour. The battery dead in my camera, I missed his portrait. Of course.

From inside the storm, I could see the swirl of winds along the margins of the down-bursts where a swarm of dust devils raced ahead. Thinking this possibly a dream, I pulled my jacket on and packed up. I was two miles from the summit and had a mile and a half, give or take, to walk up the fan before hitting the quick slope of the mountain front. Starting out as frustrated as the coyote as the pummeling continued, I suddenly walked from the squall onto dry ground and into the calm on the storm’s back side. Odd and beautiful.

It is an easy walk up the two-track past some mining prospects to the moderately steep, cross-country climb to the hilltop ridge. I am back in the wind, more squalls climbing the western front of the range where views are truncated by curtains of storms. The isolated downbursts leave tracks of graupel in their wakes, like the wet trails of snails on a morning sidewalk. I can see my truck in the midst of a well-marked storm-track on the desert floor; the track at my truck seemed the most prominent, but it was accompanied by multiple white tracks across the valleys and up mountain sides. This is not something I had experience previously and would not have had the vantage point to observe the tracks if I had not been on a quest to this relatively minor Nevada high point.

On the ridge, which I thought would hold the high point, I noticed that an abrupt hill to the north was higher, if only slightly. I dropped into a swale and then climbed again to gain the actual high point, finding a little cairn where a small jar held a few pages of a rarely signed summit register. It had been a couple years since another visitor had signed in.

Storms continued to track the desert below me, leaving ephemeral white trails as they ran. I seemed to be standing just below the clouds and the wind tried in vain to push me northward. I needed to drop southward on my return, and into the leeward shelter of the hillslope I went. Number 80 on my list, some 272 left to visit. Summiting the Cuprite Hills, and other minor bumps in Nevada’s mountainous landscape, is not an impressive feat of mountaineering – it is not even a difficult walk, but when conditions are right, these small hills provide an experience equal to, or surpassing, any climb I have done. This was a good day, and I am glad to have taken a few hours out of my drive to enjoy these mostly unnoticed hills of scattered yucca, where the storms race to the horizon and dust devils dance in snow.

Please subscribe for monthly (give or take) updates and news of upcoming excursions and projects.

Keep going.

Please respect the natural and cultural resources of our public lands.