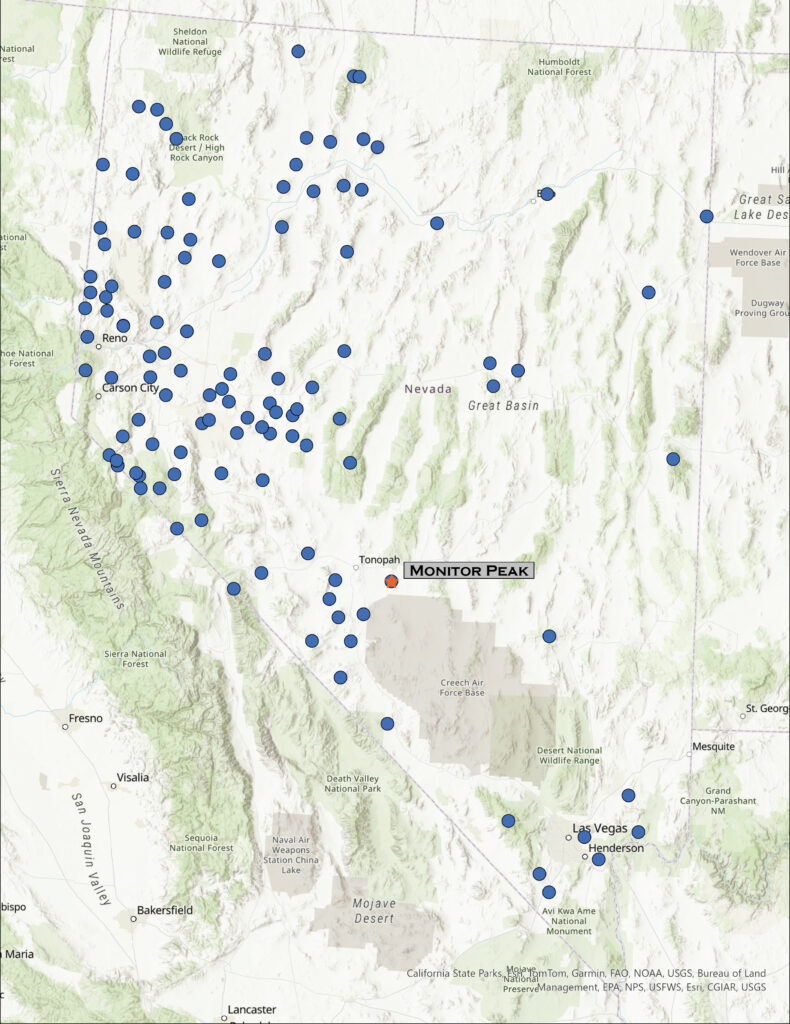

A missile, about 10 feet off the ground, marked our turn. I have driven many times past this lonely missile mounted on a pole next to Highway 6 east of Tonopah, Nevada, always wanting to take the turn and head south. There is a secured gate several miles further, but we were headed to the Monitor Hills, and not this secluded entrance to the Nevada Test and Training Range. Clear skies preceded us, and yet we had been driving through an early morning that varied between fog, rain, and snow. The weather followed closely, overtaking us as we parked at the foot of the small range.

Monitor Peak is a nice, isolated hill with a lava-capped summit on a foundation of eruptive tuffs and relict fans that eroded from an ancient mountain range that this younger volcano pushed through million years ago. However, I had to mention the missile for a bit of excitement, because Darren and I, while having a good, snowy walk, reached the high point after a short, simple walk up a small canyon and quick traverse to the rolling summit. It started snowing as we started walking. I have hiked so many high points and have rarely had an inclement adventure on any of them, though I do not plan according to the forecasts – I would like an adventure or two with some dramatic skies to photograph. In the Monitor Hills, however, we had no views from the summit, while the snow fell gently as fluffy flakes falling slowly through a misty fog. It was a pleasure, but there is not much of a story to tell – the old missile looks as aggressive as any aerial weapon, but it is rusty and inert, of course, and basically a contractor’s sign for work on the test site.

We walked across the tuffs and flows through a thin veneer of last week’s snow. Today’s precipitation would not amount to much. Bunch grasses poke through a sandy mantle, while shadscale and other small shrubs grasp to the shallow desert soil, here and there. Ground squirrels and probably a few kangaroo rats track the snow, burrow to burrow. It looks like tracks of horned larks cluster around some of the larger bushes, but I am not really sure what species might have left them, just guessing at the usual suspects given all seem to be hunkered down elsewhere.

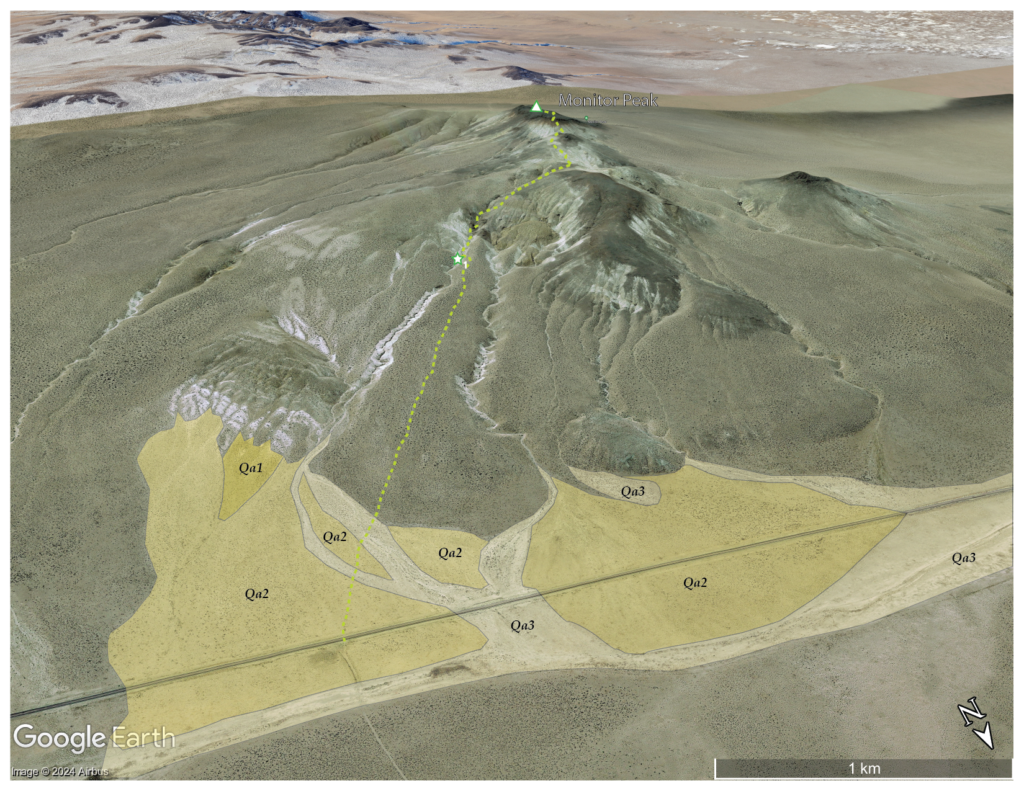

Near the base of the hills, a series of recent alluvial fans forms as sediment is intermittently eroded from the short canyons cut through relic slopes of the uplifted hills. I can map these based on cross-cutting relationships where younger fans overlap older deposits. Although we noticed minor changes early on our walk, before we reached the sand-covered tuffs and conglomerates, I mapped the young fans later using aerial imagery of Google Earth.

The fans and active drainages, the local alluvial system, is number 1 to 3, oldest to youngest; Qa is a common label for Quaternary alluvium, so Qa1, Qa2, and Qa3 — older fans to young fans and the active washes. I could be more or less detailed depending on the questions I might be asking or patterns I want to illustrate. Also, given that the Quaternary is basically the past 2.2 or so million years — that is a long time, including both the Pleistocene and Holocene (and maybe the Anthropocene), I typically stick with this labeling even though I am primarily focused on the Latest Pleistocene, from the last couple ice ages to the present – less than 5% of the actual Quaternary – for mapping purposes. This is the time when processes driven by climate, tectonics, and gravity established the backdrop and influencing the formation of the region’s archaeological record.

These are the silly things I think about, while trying to take a few pictures and walking in the snow. Where nothing moves but slowly falling snowflakes.

And nothing moves on the road, it is only us and the snow – the snow that vanishes as we return to the truck. One intense rain squall and the skies break to scudding clouds and occasional glimpses of distant sky. The wind replaces everything – it is a long drive home. My curiosity about the road marked by the missile sated, I can look forward to another high point and, maybe, more interesting weather, like today, when the walk is easy and landscape is quiet.

Keep going.

Please respect the natural and cultural resources of our public lands.