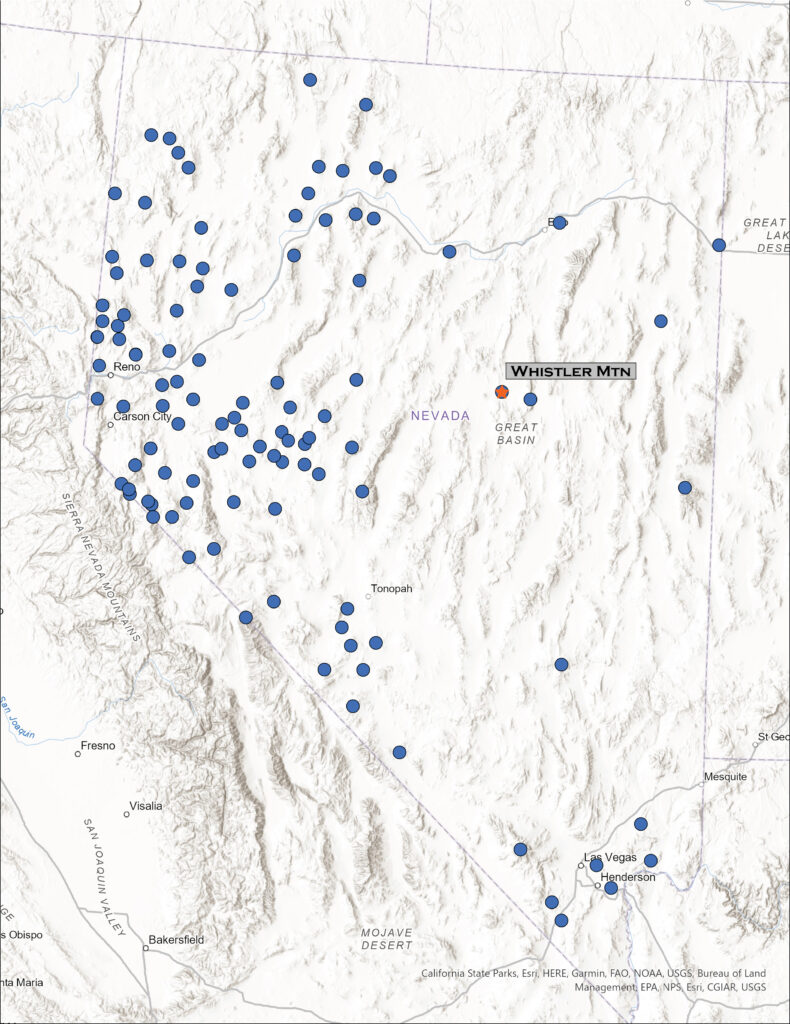

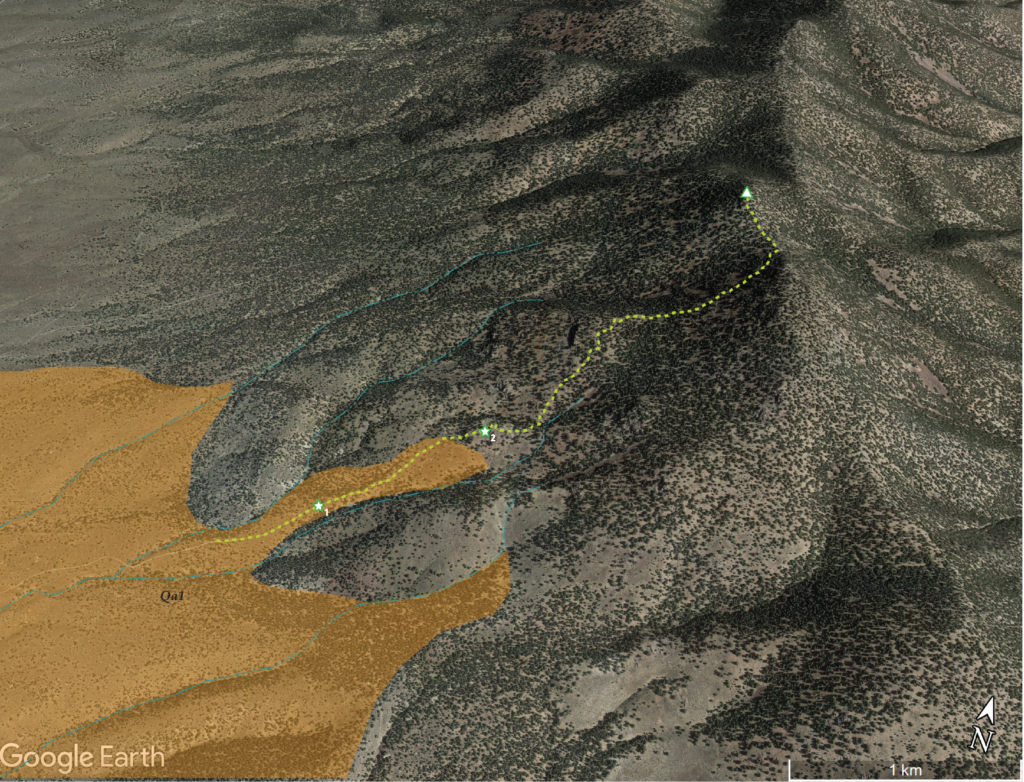

I have been on a mapping excursion, developing an archaeological sensitivity model on a cross-section of Nevada, basically paralleling Highway 50. Setting camps along the way, it sometimes puts me in proximity to high points on my target list, and today I am up early for a walk up Whistler Mountain, a small mountain range rising between Diamond Valley and Kobeh Valley in central Nevada. West of Devils Cut, a prominent cut in ancient seabeds rising in gray stripes of limestone, I turn across Slough Creek to traverse along the base of relict fan lobes before turning eastward and upward on a two-track road leading into a relatively dense pinyon-juniper woodland. The relict fans transition from dissected alluvial lobes to erosional surfaces that bevel limestone rocks – the same rocks tilting skyward at Devils Gate. The limestone, however, is not evident on the pediment landforms which are capped by a veneer of alluvium, which I can only map generally as a local Qa1. I will not see any landforms of more recent age once I begin my hike, so given that my typical focus is on landforms of recent age (<25,000 years ago), my map for Whistler is not very informative.

While mountain hillslopes are generally not the place to be looking for recent processes of scale, beyond landslides and occasional glacial features, the conveyor belt of water and wind begins in the rocky outcrops of steep country. The sediment of the valleys and their margins begins somewhere. And, it is a nice morning for a woodland walk all the same.

I leave the truck soon after the woodland thickens to close in on the two-track, probably once an access for wood-cutting to support charcoal production necessary in the mining areas around the town of Eureka, Nevada. Walking steadily upward, I am soon among cliffs of intrusive rocks, similar to granite, that moved through the older limestone rocks and now form the bulk of Whistler Mountain. Any eruptive lava (extrusive rocks) that the intrusive rocks may have once fed toward the surface of any ancient volcanic landscape have been long eroded away. I notice, however, among the wildflowers still thriving in our mesic, extended spring, small scale surface features that contribute, ever slowly, to the conveyor belt of sediment that builds the dynamic landforms of the valley bottom. It’s the little things.

Windloads of dust settling on mountain sides across the Great Basin, forming the dusty sediments where stir up on just about any walk or ride. While these often settle into the shallow soil column, they swell when saturated by winter snowmelt and occasionally begin a viscous flow when the combination of water and slope is just right. These little water-logged landslides begin the transport of sediment, carrying larger rocks along with them, moving a meter a year, here and there, to begin the redistribution of material basinward. The small features mimic larger slides where sediment transport is sudden and, often, catastrophic. This is a pattern – the small mimicking the large – that often helps us understand the geomorphology of vast landscapes formed over long periods of time. I love this stuff.

It does not take long to reach the ridgeline as I climb among talus and outcrops, enjoying the views of Kobeh Valley and the dolomite and limestone in the bright white of Lone Mountain to the west. I turn north toward a steeper slope that leads to a large summit ring, where some tumbledown lathe and wire marks an old survey marker. I cannot find a summit register, but there is a strange spiral-bound journal with seemingly endless hand-written lines petitioning Zelda – the video game character (I googled it) – for an endless stream of interventions and aid. It is beyond me, but maybe not the most surprising thing I have come across in a stone cairn in the backcountry.

The morning is warming nicely, and I have a lot of ground to cover today, back among the dynamic landforms of the valley bottom. I come across a series of relict charcoal platforms on my way down; evidence of why there are several ironically overgrown roads and trails, along with sawn stumps, cutting through the now-rejuvenated woodland. If this anything like the woodlands around the mining towns of Virgina City and Silver City, the mountains were bare by the close of the 19th century due to the need of charcoal for ore processing and daily life. It is also why the woodlands of today are of a generally uniform age after the hard work of pinyon jays and their peers through the intervening 120 years.

A jackrabbit bounds away from the shade of my truck as I return. I end another short hike to a small mountain in a somewhat obscure group of hills that culminate in Whistler Mountain. It is good to explore the small and the large, where patterns are repeated and new things found as we explore the high points and get into the lesser known reaches of Nevada’s Great Basin Desert.

Keep going.