Mount Irish

8473 ft; 2665 m. 2200 ft gain.

2021.04.11

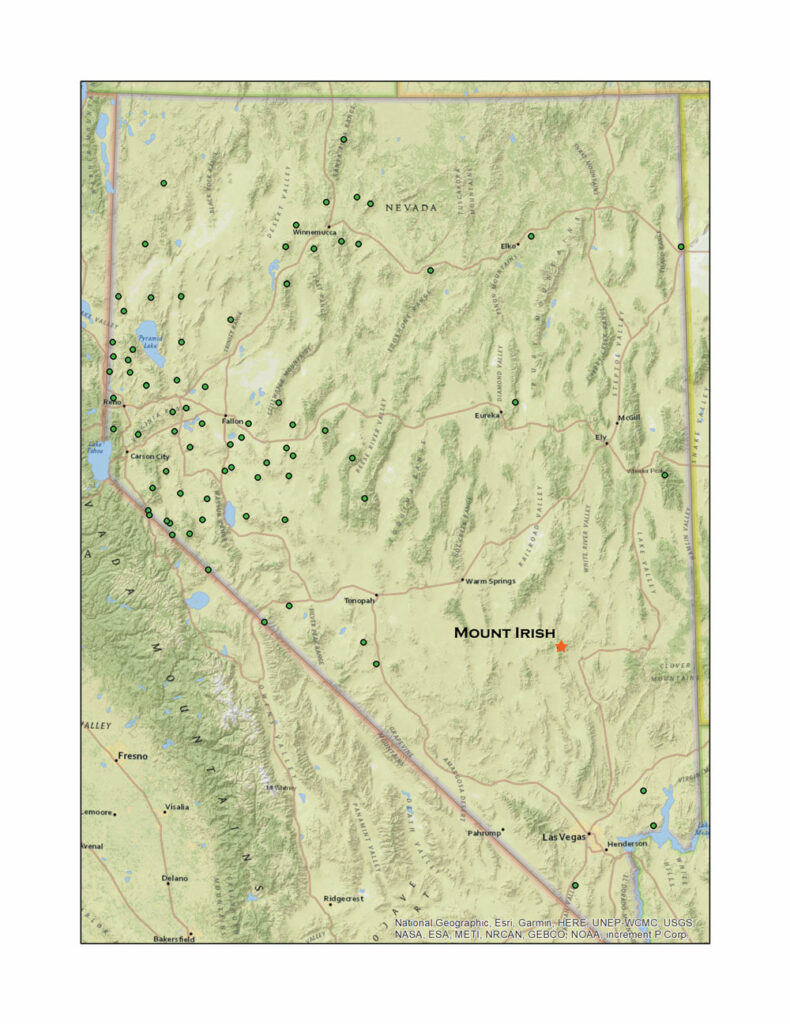

It is April’s Second Friday, so that means it is time for a backcountry recce, but first, I get vaccinated. It is my second shot. Although I had no side-effects other than a sore arm the first time around, I thought it better to wait a day to begin our excursion to Mount Irish in central Nevada. Again, no echoes from the vax, so we took off early Saturday for a camp at Cold Springs below the peak’s western slopes.

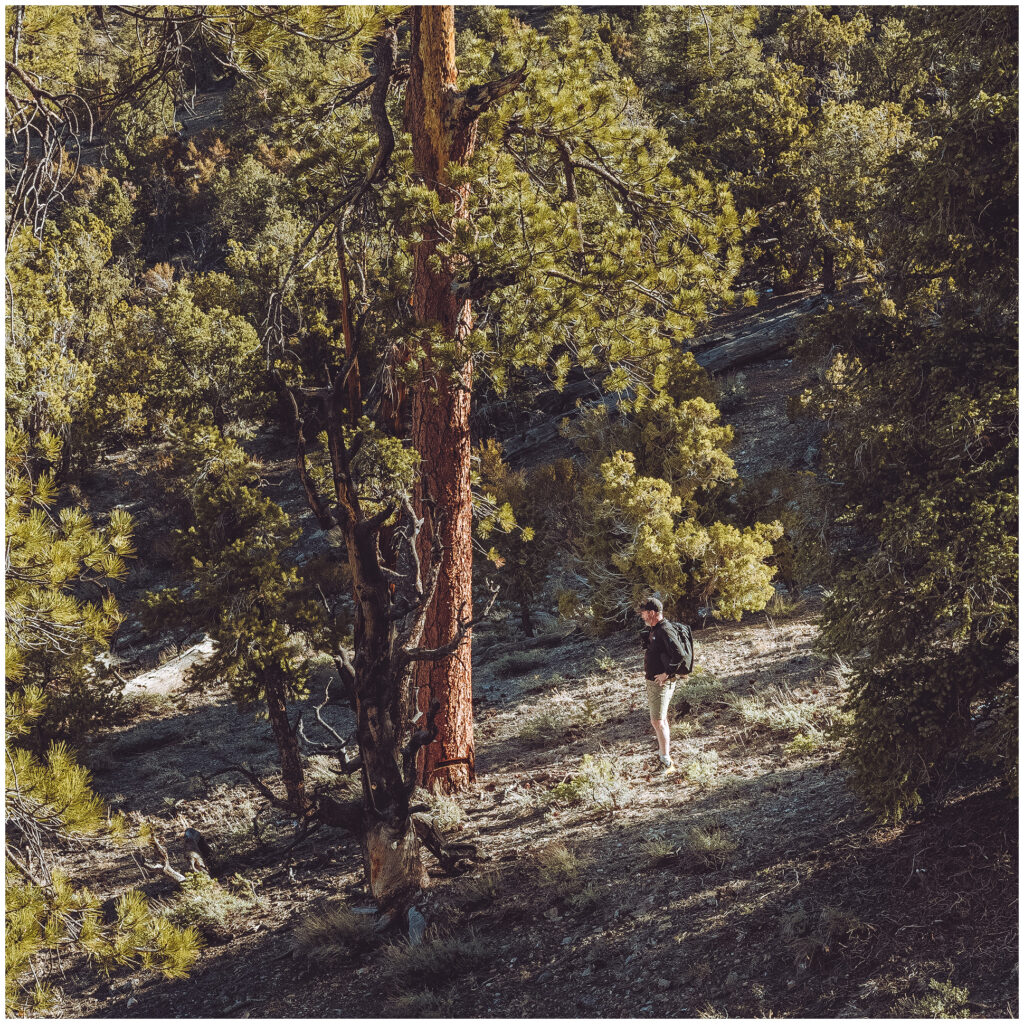

Leaving the general chaos of Highway 95 at Tonopah, we traverse the Extraterrestrial Highway to Sand Spring Valley, the playa basin of the Little A’le’inn and Rachel, Nevada. Our drive has put us close to the Tempaiute Mountain obsidian source – I continue to map and document these for Obsidian Traces, a geography of obsidian and landforms in the Great Basin. We located obsidian nodules on the east side of Sand Spring Valley and worked our way to well-preserved remnants of the eruptive event that produced this unique source of volcanic glass. After some time, we continued overland on the track that is the Penoyer Spring Road to intersect Cold Spring Road at the foot of the Mount Irish Mountains. Finding a clearing in the pinyon-juniper woodland, we set camp as a Black-chinned Hummingbird (Archilochus alexandri) greeted us.

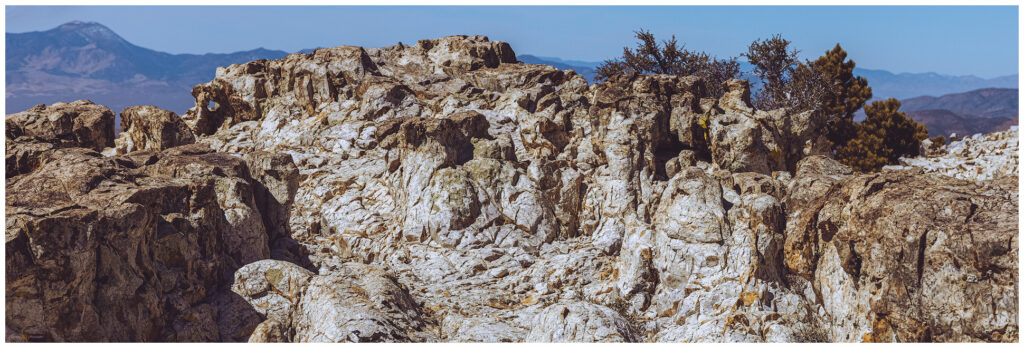

We watched the sunset reflected by Mount Irish, where summit buildings – transported by air, there is not a road – punch the skyline. I would not say they ruin the view, but the white structures and radio towers clearly detract from the otherwise quiet views of unbroken mountains. Mount Irish rises to 8743 feet, hovering over the White River Valley, a sometime connection to the Colorado River. While other basins hosted lakes of various sizes and shapes in the Late Pleistocene (and later in the Holocene too), Mount Irish looked down on a Colorado River tributary, a narrow corridor whose outflow made the eastern slopes of the mountain – and a large area of south-central Nevada – part of a drainage system outside the Great Basin. But that is the recent stuff. The limestone of Mount Irish is a basin-and-range faulted sequence of sedimentary rocks laid down in a vast inland sea many millions of years ago. Several mountain-building episodes later, the shattered stratigraphy of the ancient seas is revealed. Pinyon-juniper woodlands reach toward the summits where Jeffrey pine and white pine grow on plateaus and in rocky cirques.

Sunrise finds us cresting Logan Pass, having driven a mining road that crosses the southern slopes of Mount Irish. We climb directly along a southern ridge toward the rampart of limestone that rises in two monster steps. A series of cairns hints at a trail, but these could also be mining claims, so our direction and their general orientation may be a coincidence. However, the occasional oddly piled stones suggest routing markers. Abandoning (or losing) the markers to focus on the ridge, we target a notch in the upper limestone step. The gap brings us into a woodland basin below the high point. We traverse below a southern summit to then climb a steep slope to the altered, capping bench that is the Mount Irish summit. The structure hum with electricity powering communications and weather facilities, accessible only by helicopter – a windsock flutters nearby.

Ignoring the white buildings and vibrating antennae, the summit views are splendid. There is barely a wind, and even fewer clouds, so we hang around for a while. Photos and drone flights document and translate the scenery. I find the names of some good friends in the register, remembering that Steve and Cheryl sent me a text on their summit day several years ago. I returned the summit greeting with a similar send, and then it was time to descend. We wrapped around the eastern slope of the southern summit and came across a limestone tableland, the top of the great step into the sky above Logan Pass and the drop to the fans of the White River. Navigating to a break in the wall, we followed scree slopes into deeply carved gullies. We came out east of the pass and hiked up again to find our rig where we left it a short time ago.

I finally have a Lincoln County peak! Although not the county’s highest, its prominence above the surrounding valleys makes the views a pleasure. And, I pass a little milestone of having climbed a high point in each of Nevada’s 17 counties (that is, 16 counties and one independent city – Carson City has the former footprint of defunct Ormsby County). I digress. This is a beautiful desert peak with a great mix of steep hiking and woodland walking; the cliffs provide drama and strength, especially in the morning light. It is definitely a worthwhile climb.

Our trip home becomes the more adventurous portion of our journey. Upon returning to camp, I notice the tow-ball and its attachment have separated. Somehow, the bolt and lock-washer securing the ball to the receiver-insert have fallen off in camp; after having traveled the previous day and all morning (without the trailer) in a rather precarious position. All parts accounted for, we torque the bolt into the ball, but it is not as tight as I would like due to recent damage. We can roll, but we stop and check it regularly on our drive home. We finally get a tight fit in Tonopah, where the trailer position allows the ball to lock while we apply a wrench (always keep the toolbox handy). We are back to StoneHeart in late evening, with the trailer still behind us.

Keep going.

Please respect the natural and cultural resources of our public lands.