It looked like we had a couple days of good weather ahead and we planned to take full advantage. Although I had no real reason to, given the late sunrise, I was still getting up early, brewing some coffee in the lobby, backing up my remaining SD card, and loading images into my traveling Lightroom catalog. I have a small, portable harddrive tied to my Surface tablet, and I am also keeping all the images on the SD card, at least until it’s full. If I keep this up, I’m not terribly concerned about losing the extra cards—they were empty.

Hali is one of a cluster of simple, nice guesthouses that sit as satellite buildings surrounding a a common dining hall, check-in, and museum; all within a working ranch above the coastline. Our building has a common area with a few amenities, coffee, tea, and plenty of nightly beer. It is here that we gather morning and evening to share processing tips, strategize for the coming days, and basically get to know each other. The group has bonded nicely, and it’s good to have a few nights in one place.

We drive up to breakfast and as we exit the van, Thor tells me a stranger left him a voicemail last night. He says that an American couple he talked with during our shoot at the Solheimasandur plane wreck had stumbled on my battery bag, remembered Thor Photography, and deduced that some silly person in Thor’s group must have left it behind. And, it turns out, they are basically paralleling our travel route and figure we can easily cross paths in the coming days. You might think this would call for the cliché of “only in Iceland”, but I’ve experienced random, yet purposeful, acts of kindness—often revolving around my losing bits of gear—from the islands of Fiji to the jungles of central Africa. People are good.

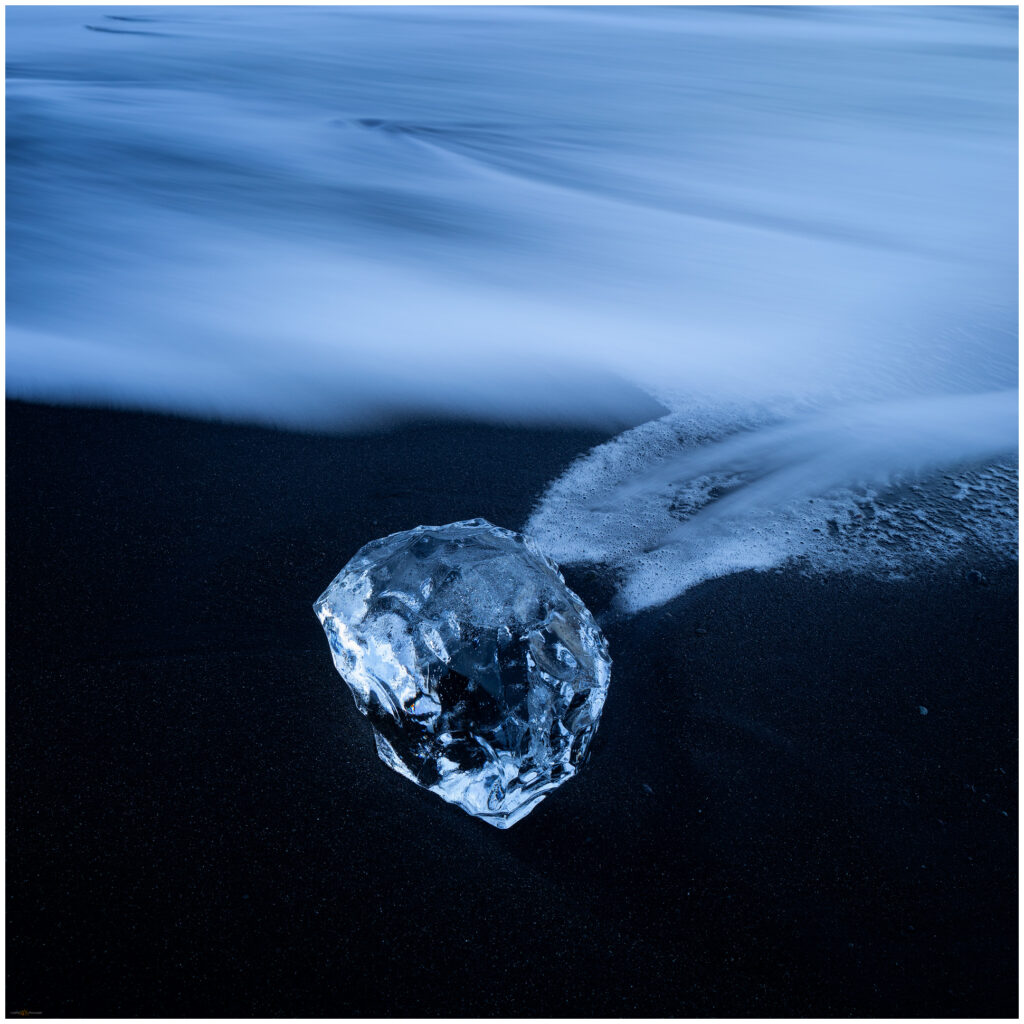

Today we focused on Diamond Beach at the outlet of Jökulsárlón. The dawn was cloudy, cool blue and grey, but breaks in the clouds teased of goodness to come. We huddled at the van with Nick and Thor for some general tips for shooting on the beach; I think these guys knew the group would soon be scattered along the beach like children at an egg-hunt. The black beach with its lag of glacial chunks and shards is one of the icons of the South Coast. I had of course seen several videos and many images documenting the multi-faceted, crystalline remnants of wave-polished ice, in sizes from bergs to tumbler cubes. Yet, it is difficult to grasp the scale and simple beauty of the setting until you begin to wander among the diamonds. A fresh coat of snow added contrast and drama to the black shoreline and its scattered crystals. We readily and greedily dispersed.

The ebbing tide and a debouching stream pull glacial bergs from Jökulsárlón, and the slowly melting ice rolls into long-shore currents to be distributed by curling waves along the black beach. Gathering and focusing the ambient light, the little bergs of ice glow against the darkness of volcanic sand. As usual, arriving before dawn, we had the beach to ourselves; remember, in the Instagram era iconic is synonymous with crowded—we were ahead of (or behind) most of the crowd, yet again. We also had the good fortune of fantastic conditions. The fickleness of storms and currents can either pack the shore with ice, creating a mish-mash of shapes and clutter, or strip it bare, leaving a simple, curving and empty beachline. It was practically Goldilocks day, just right—actually, just perfect.

Although it is an iconic shooting location, it’s first and foremost a seascape with ice. This means, unlike many icons, it is dynamic and every shot is different. However, there are basically three common compositions: 1) splashy waves surrounding and retreating around emerging bergs; 2) dramatic otherworldly crystals lit by the winter sun; and 3) intimate images of a lonely diamond on black sand. Or some slight variation on these. Several us dispersed far up the beach as the crowd grew near the easy walk-in spots. I shot in burst mode, capturing the interaction between various shapes of ice and incoming and outgoing waves. Even with intimate scenes of a single crystal, its interaction with a framing, foamy surf can make or break a potential keeper image. Getting up close, down low, and purposefully identifying the subject improve any of the three basic compositions significantly. Of course, these means getting familiar with the surf, occasionally getting into it, or even getting surprisingly soaked by it. We came prepared to get wet, and it was great fun.

We took a break for lunch. Or we didn’t. Maybe. The conditions were so good we may have simply kept going. The day was so good I honestly can’t recall what we did, if it was something other than finding new compositions and taking advantage. I do know we eventually moved inland to the lagoon—basically across the highway, where we watched a practically endless, golden-hour sunset emerge from a cloudless sliver on the horizon. Um, Goldilocks had grown up and was now lording over us—it’s not just-right, it’s wonderland (or is that Alice?). Being daytime, it was the opposite of our aurora show, but I was as gobsmacked today as I was on any previous night.

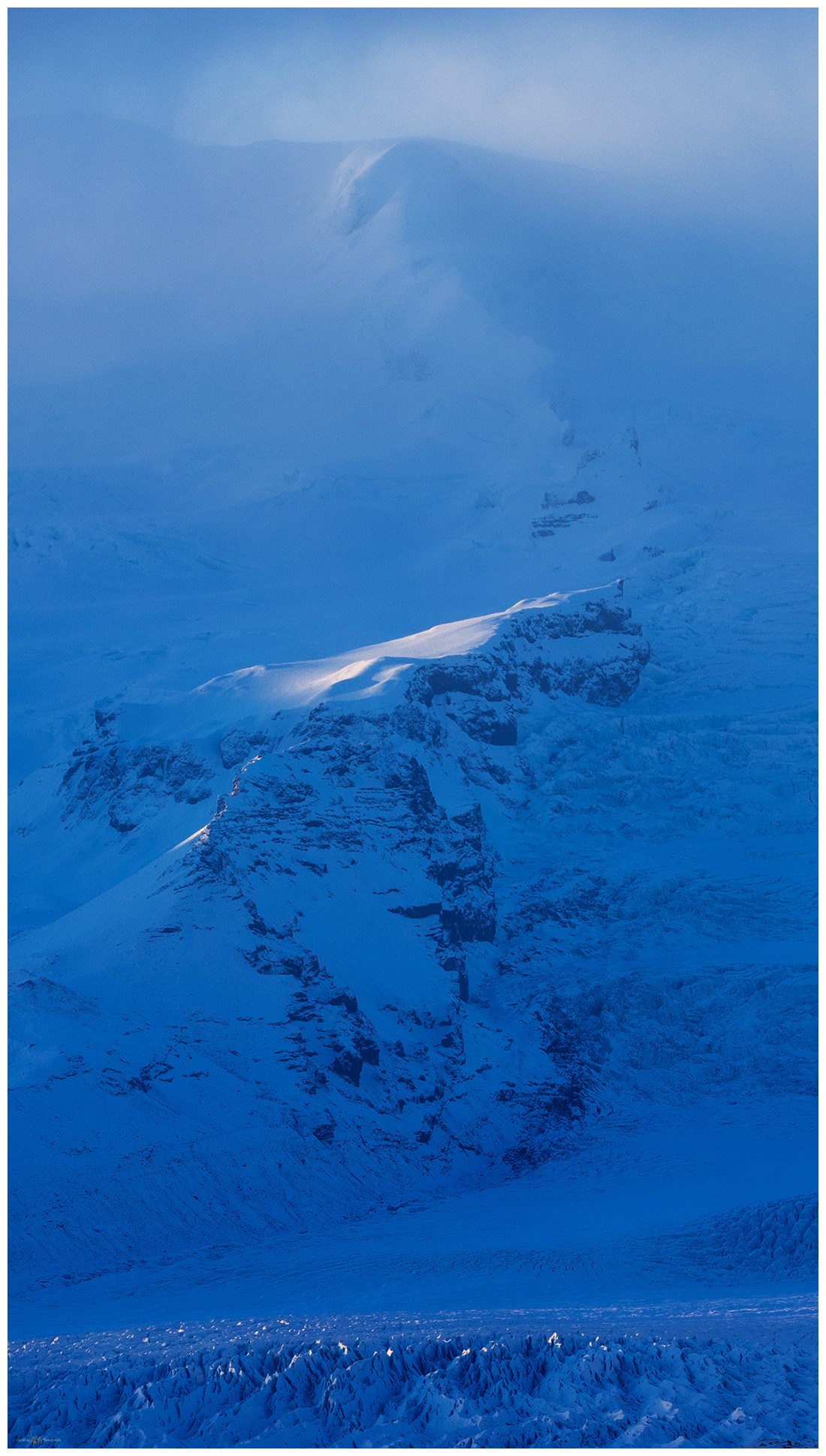

All afternoon I am overwhelmed with mountain scenes rising from Jökulsárlón—I could photograph mountains forever. But soon, I catch Nick motioning to those of us near him, he’s heading back to the beach as the sun settles into the ocean. We had spent the morning capturing the iconic compositions, getting practiced and occasionally successful at the three basics, but his instinct drove him to look for something different, something other than the popular shot. Generously, he shared a glimpse of that instinct and encouraged several of us, those of us within earshot and anyone he came across, to think about how the last light would interact with some of the snow-covered bergs higher on the beach. Maybe, by considering this, we’d get something unique to add to our successful morning. It is a common instructional tool, “look for something different”, but this was in real-time, with perfect conditions that where somehow improving, if only in the last breath of light.

Nick Page’s Photographing Iceland video

Did I translate his wisdom successfully? I think so. Is it truly unique? That’s unlikely. However, it’s definitely not the million-in-a-million images of the ice at Diamond Beach (as enjoyable and compelling as those are individually). Maybe it’s unique in a hundred-in-a-million sense. Regardless, it was about knowing (or learning) to see something new, even if you’ve only been in the perfection of the icons and diamonds for a day. Thanks Nick.

Keep going.