Our night in the overflow camp was not that bad, and we were up early covering the short distance to the iconic viewshed of Zabriskie Point. We were the first parking-area arrivals – Erno, Jeremy, Quinn, Sandy, and Randy – but were soon followed a good-sized crowd as the developed walkways of the overlook absorbed the people and numerous tripods. Despite the early morning visitors, it is not difficult to spread out and focus on some small scenes in the Zabriskie badlands while not missing out on the iconic expanse overlooking Death Valley. I climbed the hills to the north to wait for sunrise. From the small summit, I looked down on the geometric patterns written in the tilted volcanic tuffs. Odd to watch the iconic view come to life in the sunrise – a scene I had seen in so many images, and although I had passed the parking area numerous times, avoiding the crowds by never stopping, it was a good spot to take in the morning. I was glad I was here.

The weekend crowded faded into Monday morning, allowing us to move camp to empty spaces in the Texas Spring campground. We set up and relaxed into the late morning and growing afternoon. We had scouted out the area southward into Badwater Basin, selecting some locations where fine-grained alluvial fans crossed the road and extended into the bottomlands. Now we rested in camp and let time pass, making plans for the coming days. Tonight and tomorrow, we would hunt for the patterned ground of polygonal cracking – Erno kept cleaning his gear in anticipation, or maybe he kept telling Jeremy he should clean his gear. We were all looking forward to it, dust spots or not.

We spent the evening and the following morning, below sea-level, wandering the broad fans looking for compelling patterns in the mud cracks. Sediment carried by the last energy of a flash flood, maybe a year or two ago, all other large clasts dropped along the flow, creates a fine-grained veneer between gullies and rocky berms, cracking as it dries and repeating the swelling and shrinking with each new wetting cycle. We spend a long evening on the middle fans. The backdropping sky is subtle, lacking the fireworks of our previous night, but we wait and hope. The following morning, my preparation for capturing sunrise over the polygonal patterns started early. I crept out of the dark parking area, heading toward a more distal position on the fine-grained fans of Badwater Basin. Walking in the dark of pre-dawn, I wandered down-fan looking for some interesting patterns or rocks to the foreground of sunrise. It was quiet and dark, great to be walking. As dawn approaches, I see the rest of the team parking along the road as they work into the sunrise.

It is difficult, for me, to have the patience to choose one small scene in the multitude of patterns, when my typical mode is to continuously recon for profiles and exposures. This is something I need to improve. I often leave a scene too early, wanting to look around the next bend or investigate the next outcrop. It is perfectly ok and fun but creating images the speak to the experience becomes rare. I wait and enjoy the slow sunrise, playing with a few cobbles and cracks.

It is our day to take the long, looping road of washboards and rutted dust to the Racetrack Playa, always the highlight of any journey in the Desert Valley outback. We leave my trailer and Erno’s rig in our Texas Spring campsite and spend the day traveling to the Racetrack; we will camp one night at Homestake Camp and return to Texas Spring. Arriving in late afternoon, we explore the Grandstand, an inselberg poking through the northern end of the playa and then visit the tracks of racing rocks nearer the plays southern end.

It is a puzzling spectacle viewing the cobbles and boulders (and occasional sticks) with ephemeral trails marking their ‘race’. How do they move? In sum, it is the occasional and timely interaction of water, temperature, and wind. The Racetrack is a somewhat unique playa setting given the large limestone outcrop at its southern end – most playas being isolated in the middle of vast basins far from rocky outcrops. At Racetrack, the outcrop provides the rocks; as the outcrop weathers and crumbles, cobbles fall onto the playa. Winter rains drain to the playa forming dispersed, shallow pools around the scattering of rocks. Basically shallow sheets of water, the pools freeze into thin sheets in a winter’s night (our water bottles were frozen solid overnight here at Racetrack). The rocks become wrapped in the ice sheet, like peanuts in a brittle – the rocks are not submerged, protruding from the sheet of ice, top and bottom. Wind across the frozen sheet starts a cohesive drift as the ice becomes an expansive ‘wing’, acres in size. It takes only a good breeze to move the sheet, dragging its entrapped rocks as they slide and scrape along the lubricated silty clay between ice and underlying playa. All the rocks in a locally frozen pool move in concert; it is why sets of tracks look to be in parallel, matching patterns – a choreography of geomorphic process. In the sunny warmth of a coming day, the ice melts and the water evaporates quickly, leaving only rocks and their trails as circumstantial evidence on the signature dry playa. It is a wonderfully simple and simply wonderful – easily in my ‘top 5’ natural phenomena. I have seen tracks on other playas, but there is no place that brings it all together like the Racetrack. Please do not disturb the rocks, their travels begin again soon.

We set camp at Homestake, thankfully gathering around tailgates for a generous buffet. I would say it was potluck, but we were mostly lucky to have Erno as our cutting board host. Nothing better than a desert camp, tasty treats, and random beverages after wandering among the racing rocks.

Later, I tried for some late night to early morning star trails over the Grandstand, but it basically meant sitting on the very cold playa for most of the night. The stars did not align, as they say, and my results were disappointing. With little sleep, I gathered with the team back on the Racetrack. Despite of, or maybe because of, our weary, silly state, Jeremy and Sandy teamed up to choreograph the perfect group picture. Frameable and available for order, I am sure.

We traversed back through Teakettle Junction and Ubehebe Crater to arrive, at last, in our spot at Texas Spring Campground. Although we attempted some night photography at Zabriskie (hey, it was easy access after the long drive), I have not seen many team images from that night. The outings cannot all be gems, even in this group.

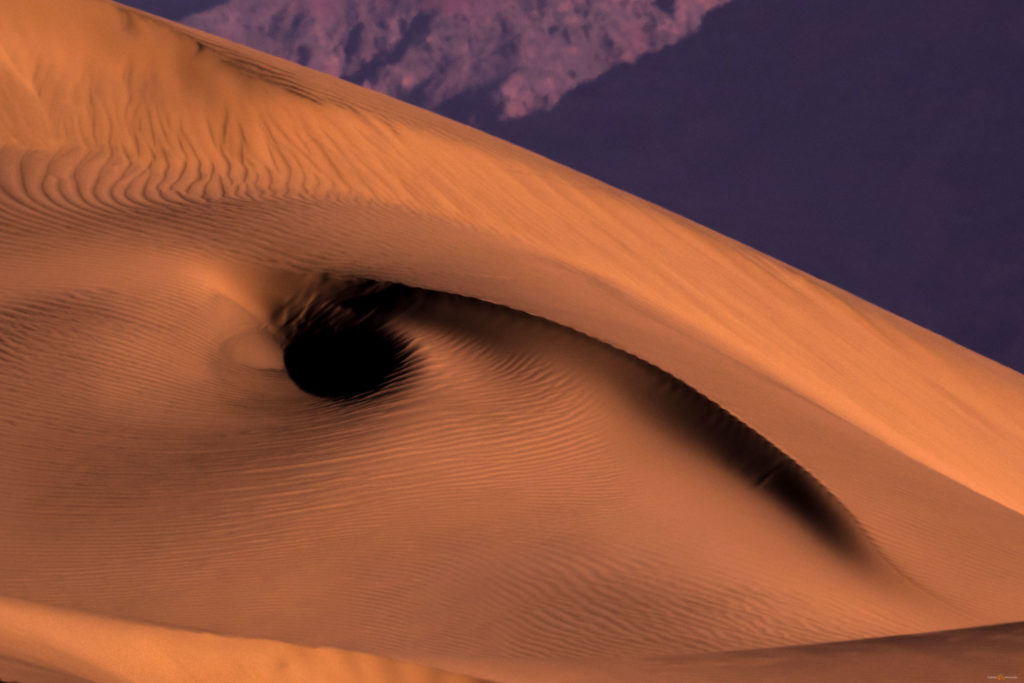

The morning was another matter. We were outbound, heading for the Alabama Hills, but we took a timely and deserved stop at the Mesquite Dunes. Sunny, calm skies forced us to turn inward, looking for small scenes in the golden contrast of the morning. We approached from the southeast to avoid the tracked-out areas of the previous day’s visitors. These dunes appear in thousands of images in as many ways, but the attraction of contrasting patterns in the ever-changing landscape is profoundly magnetic.

We dispersed and enjoyed our time before beginning our journey home. We had one more stop to make, so driving again, we emerged from sea-level to greet the valley at the foot of the High Sierra.

Keep going.

Please respect the natural and cultural resources of our public lands.