Powell Mountain

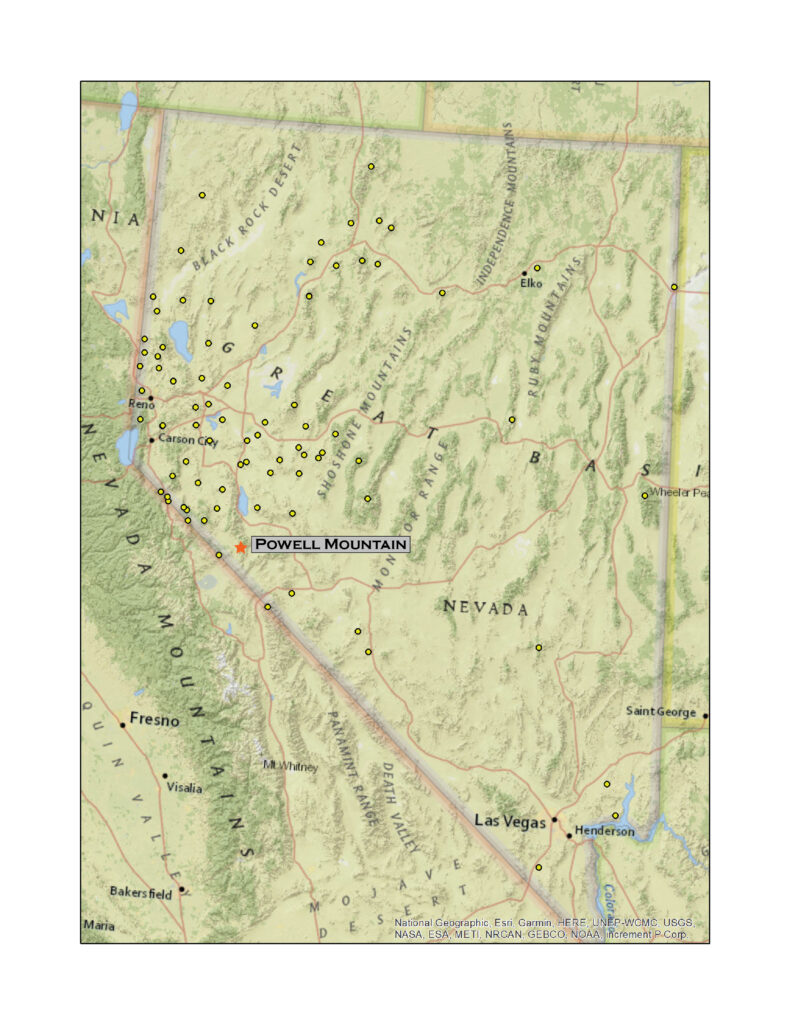

9530 ft (2905 m) – 1988 ft gain

2021.08.13

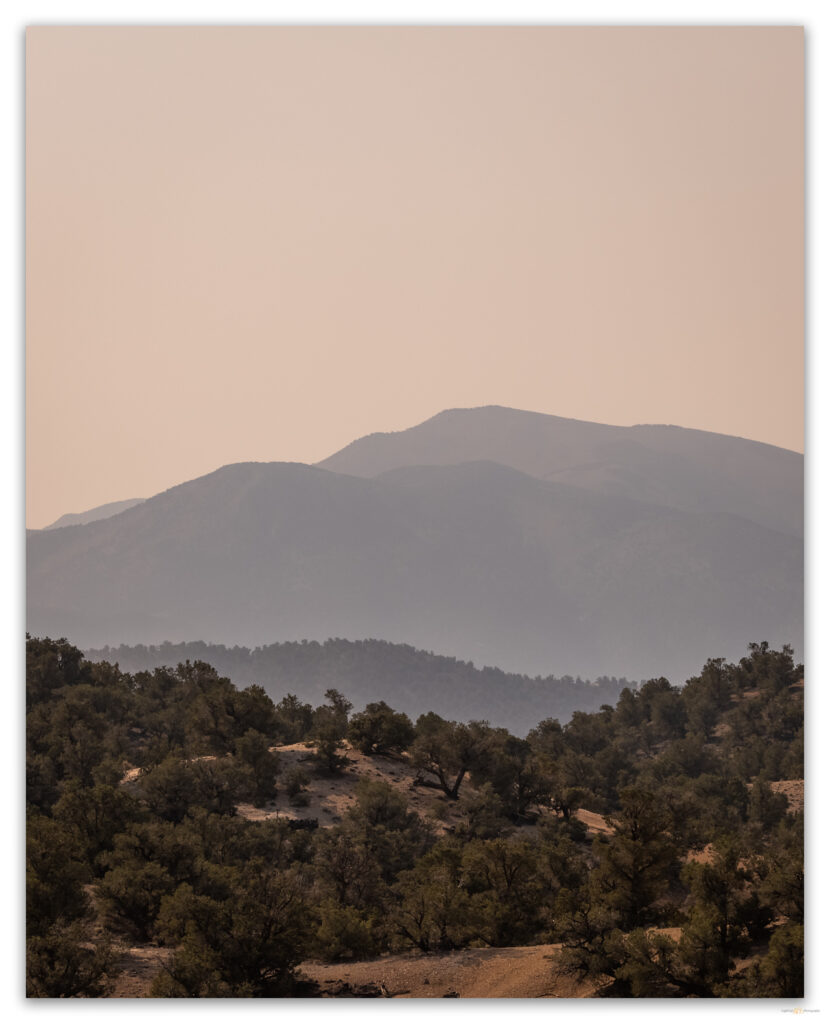

It took a long time to get going today. Smoke from Sierran wildfires has filled Carson Valley for weeks it seems – now the typical summer atmosphere, and the heat has been oppressive, forged one-to-one with the unending haze. Could I drive out of it? Climb above it? It was hard to get motivated.

The Anchorite Hills rise as an afterthought, like a comma, on the southern end of the Wassuk Range, the home of Mount Grant above Walker Lake. Low mountains of rhyolite and granodiorite host thick pinyon woodlands that give way to old fire scars where, high up, a few limber pines stand haggard and scraggly in protected canyons and bowls. I found Curleaf mountain-mahogany (Cercocarpus ledifolius) wrapping the highest ridges and extending to the range’s highpoint at Powell Mountain. However, boulders scatter among the vast areas of open Montane Zone shrubland, which makes for nice walking on open slopes, approaching ridges, and intervening hummocks.

I approached the Anchorites from the West Fork of the Walker River, following the Hawthorne Road toward Lucky Boy Pass. After watching an Osprey dance above the Walker, I skirted Rough Creek and traced along Mud Spring Canyon and its numerous tributary washes to get to the broad pediment of the Borealis Gold Mine. I turned south to cross a beveled landform cut by dry washes with clear evidence of being not so dry very recently. Detritus of sticks, weeds, and mud hung as snags in washes were bedforms showed ripples and pools of a passing flashflood. I was a day or two late, but new thunderstorms were brewing. The monsoons of recent days had been rather weak and primarily anchored to local topography – the cells built above highpoints and stayed there, mostly. I was headed for a highpoint, but it wasn’t as high as Corey Peak and Mount Grant to the north, and that was where today’s storm held its ground.

A few raindrops pelted me as I scouted on foot for a camp. I had driven the rig and trailer to a good turn-around and searched ahead for a spot that was not too tight and would not get damaged if I brought the trailer further up the two-track road. I had already made a sketchy turn-around exploring the pass between the Wassuks and the Anchorites; that track being riddled with flashflood debris stuffed into a typically good dirt road. Tonight’s camp would be below Powell Spring where pinyon-juniper woodland transitions abruptly to valley shrubland at the foot of the Anchorites. Four pinyon jays and a pair of western bluebirds checked on me as I set camp.

I had originally planned to climb the short distance to Powell Mountain – about a mile and half from and two thousand feet above camp – in the morning, but the brush of rain had cooled and cleared the skies, so I set off. If I could get through the riparian brush of Powell Spring and the canyon above it in less than an hour, I should be able to access open country and get up and back before dark. I did not want to navigate the densely enclosed canyon by the light of my headlamp.

There is a broken-down cabin at Powell Spring; it spooked me as I came through a patch of Desert rose and willows – I do not want to visit this in the dark either! The canyon was just navigable. I walked along the dry runnel of the canyon floor, climbing onto outcrops that walled the canyon to get around ‘steps’ where groundwater allowed a fluorescence of willow. Here and there, dense skeletons of willows, blown flat by the weight of a snow avalanche, possibly, blocked my forward progress. While this half-mile took quite a while, I made the steep open slopes below the summit in good time. Here, I started the difficult steps into the gravelly soft sediment, a mix of dust and slopewash alluvium, that blankets the bouldery slopes below the southwest ridge. I could reach out and touch the hillside I was climbing; it was much steeper than I expected. I stumbled between shrubs and boulders, but I quickly gained elevation.

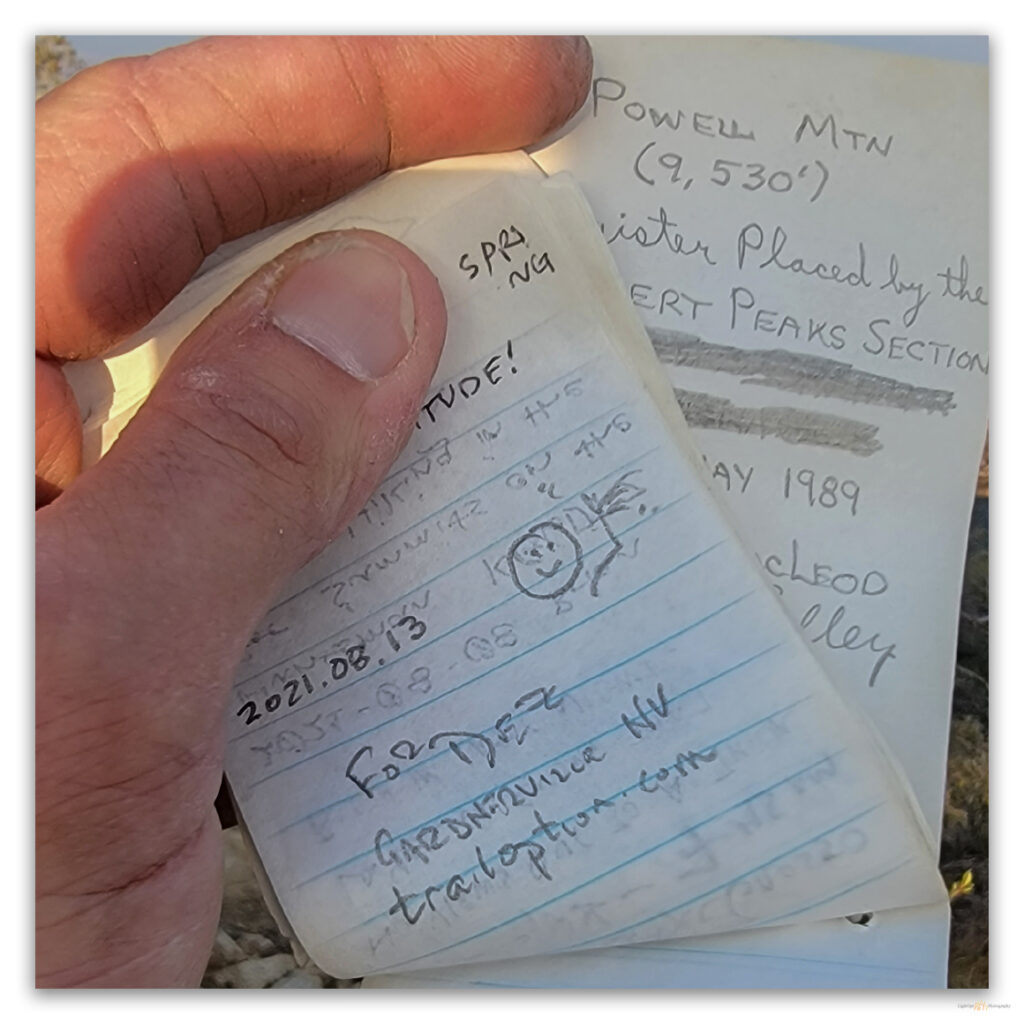

As I gained the boulder-strewn summit, I was surprised by the seemingly sudden appearance of little, packed woodlands of mountain-mahogany. It took me a few minutes to find the actual summit marked by a wood-staked survey marker hidden among the shrubby trees. The register was lost among a thicket of branches. It is not a popular summit, though I found one of the few groups to visit had hiked up here only last weekend. After signing in and watching the smoke begin to block the sunset, I knew I could not linger. I had to get through the thicketed canyon before dark.

There is some ease in descending a dirty, grussy slope. It goes quickly until a foot gets caught in root or branch, a reminder that gravity could easily win. In the steepness of the upper canyon, I startled a small owl – likely a Northern Pygmy (Glaucidium californicum) – that had been feeding on a finch-sized songbird. It was likely a recently fledged juvenile in a daily roost, benefitting from a parent-delivered meal. It was too dark for photography, and I did not have patience to wait while the canyon floor darkened.

I felt my way along the canyon floor, following my approaching footprints through the small, dry streambed. The bends in the canyon seemed to alternate from noisy with songbirds and insects to the quiet of enclosed woodland. With my eyes focused on the red of the infernal sunset, the pinyon loomed as blackened shadows, sad portents of once and future fires. As the woodland darkened, I could just make out sandy gullies in gaps between trees, arriving eventually and abruptly at the imploded cabin below the spring. It was time to get the headlamp out, but I enjoyed the last few steps to my truck, happy to have had the summit walk at the end of a slow-starting day.

Keep going.

Please respect the natural and cultural resources of our public lands.