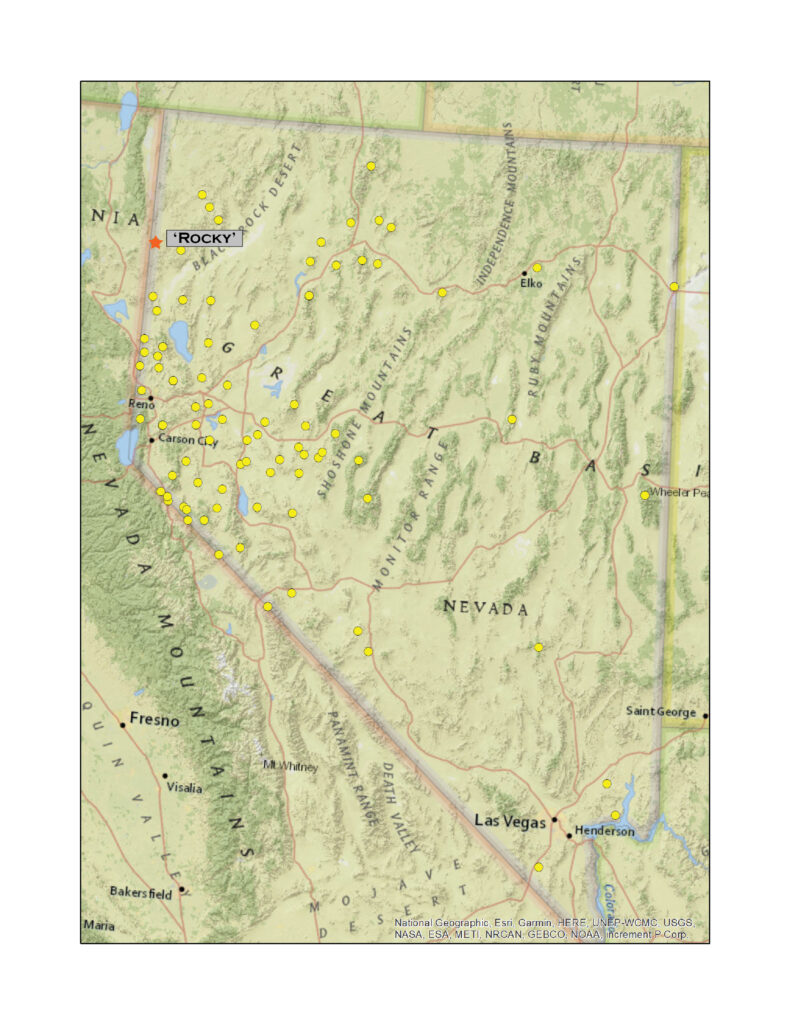

Rowland Mountain (‘Rocky’)

6911 ft (2107 m) – 650 ft gain

2021.09.24

The mornings have the feel of autumn, but the midday still holds the heat of summer; it is that time of year. Here, at the close of September, I had a landform mapping project in support of archaeological survey and inventory near the northern end of the Madelin Mesa, a hardscrabble and fire-altered tableland that stretches along the Nevada-California border in northwestern Nevada. You could argue that this is not a mountain ‘range’ at all, but the basalt-capped rimrocks and plateaus are punctuated by a few hills and form a distinct region between Buffalo Creek and the Madeline Plains of northeastern California. I have driven by Rowland Mountain for many years, gouging around between the Hwy 395 corridor and the obsidian-rich calderas of the High Rock Country, and, though I had created my list of target high points quite some time ago, I had forgotten which outcrop was the high point. It is a simple cluster of basalt outcrops just south of Buckhorn Road.

Darren and I had tried to get to Rowland in March, but our plans were curtailed by poor road conditions. On that outing we had retreated from the mesa and made for the High Rock Wilderness, drier land to the east, and summited Mahogany Mountain.

This time I was alone, although I knew of an archaeological field crew camped a few miles to the north. I was on my way to visit them, but first, with no sign of snow or much of anything to block my way, I turned toward Roland. I parked near an older Wilderness Study Area (WSA) boundary sign, though the currently mapped boundary of the Buffalo Hills WSA, is along the summit of the nearby ridge – this is the goal of today’s summit walk.

It seems we have had endless days of cloudless skies. This can make for a pleasurable outing, but it makes the creation of interesting landscape photographs challenging. And, while landscape photographers have been trending away from grand, saturated landscapes toward smaller and more personal compositions, I remain drawn to the big scenes and have found only rare satisfaction with intimate, unique imagery. Maybe the cloudless walks into unassuming hills like those of the Madelin Mesa provide a laboratory for practice.

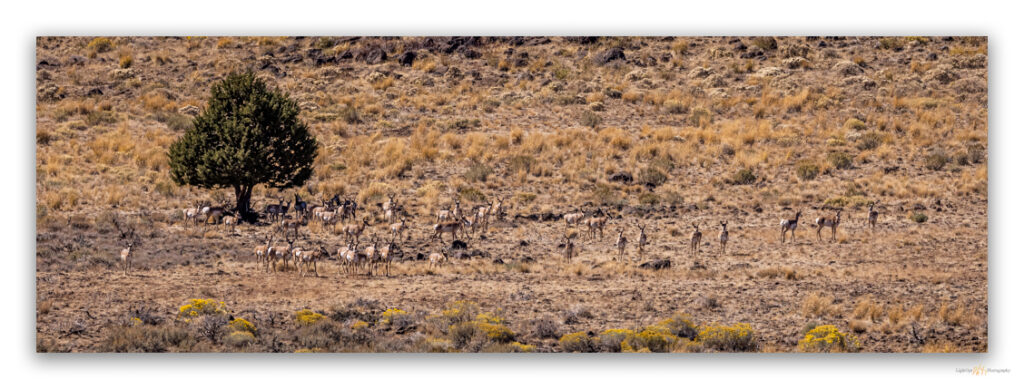

Wildfire scoured the area sometime in the past decade or so. Stands of western Juniper have become confined to the narrow canyons with patchy remnants only thickening to the north. Skeletal woodlands stand bare among the disturbance colonizers and locally proliferating – slowly, slowly – communities seeded to rehabilitate the barren slopes and washes. Curl-leaf mountain mahogany grips the higher outcrops where its fire hardiness has protected isolated stands. These hardwood trees are beginning their brief dance of autumn color and stand hopefully dressed among the rocks. Otherwise, the landscape is a trodden yellow-brown in all directions. Horses navigate repeatedly and hopefully between water reservoirs (many now dry) constructing a web of inter-weaving trails, pounding the fragilely submissive, droughty land to dust. Pronghorn look at the equine map with confusion but remain ready to run, they need no habitual track.

I reach the wrong summit after a relatively short walk. It is only a slight mistake as the elevation of the bunched-up outcrops along the summit ridge is difficult to discern. I jump off one to gain another, then another. Soon, the brass benchmark ‘Rocky’ (the label on the 7.5’ quadrangle map) shines into view. The register was placed, once again, by my ‘peak neighbor’ Tom Rountree, a summit hiker I have run into many times but never met. There are only two other names in the little book – by the looks of it, these Spanish surnames suggest visits by Basque or Hispanic crofters who could not keep from getting to the highest point around; at heart, they are no different than I am.

This walk only takes a couple hours, but I take my time, watching Northern Flickers attack the barkless juniper snags while pronghorn stand guardedly in the shad of a long western juniper until I make a careless move, and they begin a slow but purposeful walk westward away from the strange figure on the hillside.

After so many outback days generally alone, I am surprised by a cluster of hunters on my walk out. I see them a ways off, but am surprised nonetheless. Their sight of me is equally surprising, especially given that I am non-motorized, just a guy walking down a wash. I am waiting at the gate, having kindly opened it so they can pass unperturbed by its presence. I offer that I have been waiting a very long time for their arrival, and we have a good laugh and short conversation about the convenience of a backcountry valet, especially on a Thursday afternoon in the middle of nowhere, as they say. Once again, to me, this is the middle of everywhere. The best place to be, even if it hardly draws attention on a map.

Keep going.

Please respect the natural and cultural resources of our public lands.